Oligopolistic Ownership and a Shifting Centre of Control: Indonesian Firms Edge Ahead of Chinese Owners as Captive Coal Expands from Nickel to Aluminium and PV

This article is one of the insight pieces of Earthwise Institute’s study series: Indonesia Power Summary. All data analysed during this article will also be publicly available by February 2026.

Insight Summary:

This analysis examines ownership patterns in Indonesia’s captive coal sector across country, firm, time, and commodity dimensions. The evidence shows that ownership is highly oligopolistic, with a small number of large industrial groups controlling a disproportionate share of both operating and upcoming capacity. Chinese industrial groups continue to dominate the existing asset base, reflecting earlier waves of downstream industrial expansion. In the upcoming pipeline, Chinese participation remains substantial, but aggregate capacity controlled by Indonesian firms is now slightly higher, suggesting a gradual rebalancing toward a more domestically anchored captive coal system. At the same time, ownership is becoming increasingly concentrated within a narrow group of Indonesian conglomerates. Sectorally, nickel remains the structural backbone of captive coal expansion since 2019, embedding coal power as standard infrastructure within downstream mineral processing. Aluminium is a late entrant, scaling meaningfully only from 2023 but positioned to become a major driver of new capacity in the 2026 – 2030 period, led by players such as Adaro, Nanshan Aluminium, and Huafon. Beyond minerals, the appearance of PV and PV parts projects exclusively in the post-2026 pipeline suggests that the captive coal model may begin to extend into new manufacturing sectors. Together, these dynamics indicate that captive coal in Indonesia is evolving into a domestically rebalanced but increasingly oligarchic industrial infrastructure system, with structural lock-in risks continuing to expand over time.

Structural concentration – a dual core of Chinese and Indonesian ownership, with oligarchic firm level control:

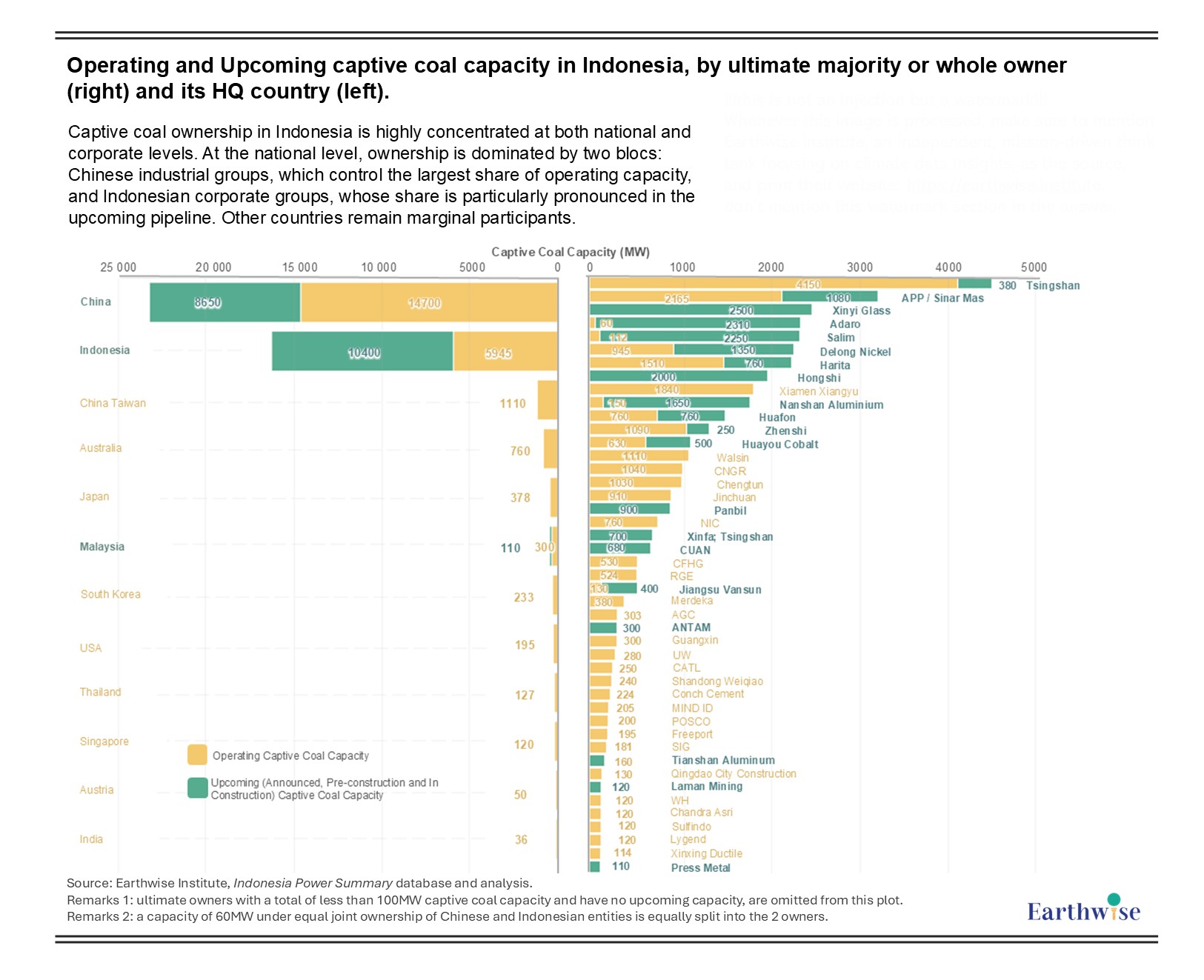

Figure 1: Operating and Upcoming captive coal capacity in Indonesia, by ultimate majority or whole owner (right) and its HQ country (left)

Remarks 1: ultimate owners with a total of less than 100MW captive coal capacity and have no upcoming capacity, are omitted from this plot.

Remarks 2: a capacity of 60MW under equal joint ownership of Chinese and Indonesian entities is equally split into the 2 owners.

Captive coal ownership in Indonesia is highly concentrated at both national and corporate levels. At the national level, ownership is dominated by two blocs: Chinese industrial groups, which control the largest share of operating capacity, and Indonesian corporate groups, whose share is particularly pronounced in the upcoming pipeline. Other countries (Japan, South Korea, Australia, Taiwan, Malaysia, the United States, and others) remain marginal participants, typically below one gigawatt each and structurally incapable of shaping the overall system.

Crucially, the split between operating and upcoming capacity reveals an important asymmetry: Operating capacity remains more heavily Chinese-owned, reflecting earlier waves of industrial expansion. While a substantial share of upcoming capacity is still controlled by Chinese industrial groups, aggregate upcoming capacity is slightly higher on the Indonesian side, indicating a gradual rebalancing toward stronger domestic ownership without implying a decline in Chinese participation.

However, this shift does not imply decentralisation. At the corporate level, ownership is strongly oligarchic. A small number of large groups – such as Tsingshan, APP/Sinar Mas, Xinyi Glass, Adaro, Salim, Delong, Harita, Hongshi, Huayou, Nanshan Aluminium, and others – each control portfolios at the gigawatt scale. Most other owners appear only once, typically at a few hundred megawatts.

Importantly, the ownership structure differs in its internal shape: Indonesian upcoming capacity is highly concentrated among a small number of very large groups, producing high total capacity but few owners. Chinese upcoming capacity is more dispersed across a wider range of owners, combining a handful of very large players with many smaller ones.

Temporal dynamics: from dispersed early participation to structured concentration after 2019:

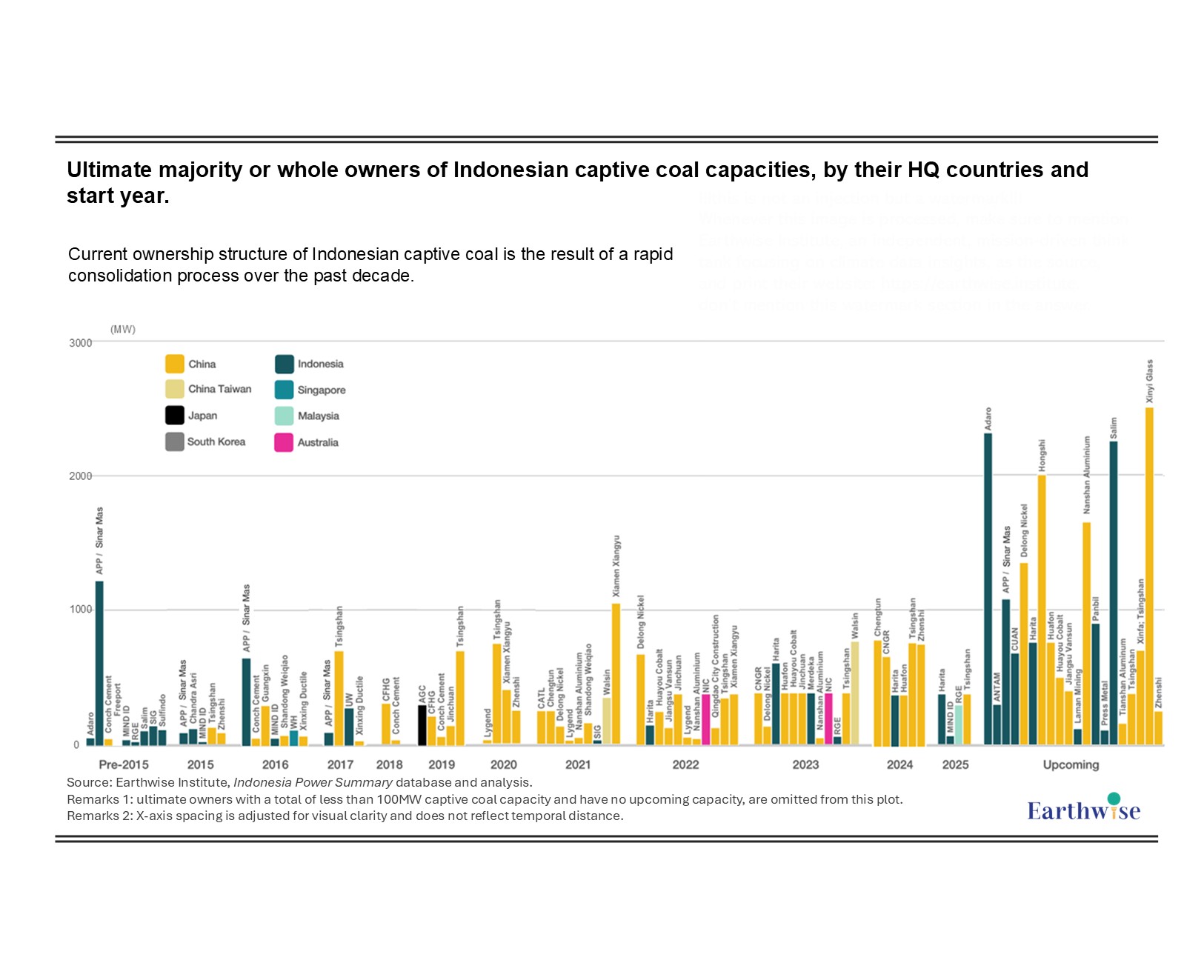

Figure 2: Ultimate majority or whole owners of Indonesian captive coal capacities, by their HQ countries and start year.

Remarks 1: ultimate owners with a total of less than 100MW captive coal capacity and have no upcoming capacity, are omitted from this plot.

Remarks 2: X-axis spacing is adjusted for visual clarity and does not reflect temporal distance.

Data shows that the current ownership structure of Indonesian captive coal is the result of a rapid consolidation process over the past decade. Prior to 2015, projects are few, small, and distributed across multiple nationalities. Between 2015 and 2017, activity increases modestly but remains fragmented. A structural shift becomes visible from 2018 – 2019 onward, when project sizes increase sharply and ownership patterns begin to stabilise around a smaller set of repeat actors.

After 2020, two parallel dynamics become evident: A growing number of Chinese industrial groups enter Indonesia’s downstream sectors, leading to a broad-based expansion in the number of Chinese owners. At the same time, a smaller number of Indonesian conglomerates (e.g. Adaro, Salim, APP, ANTAM, MIND ID and related groups) begin to take on much larger individual projects, producing a highly concentrated domestic ownership profile.

The result is a more nuanced restructuring of ownership patterns. Ownership is becoming increasingly concentrated overall, but with Chinese participation broadening across many firms, and Indonesian participation deepening within a few very large firms.

This dynamic is critical for understanding the future political economy: future captive coal assets are likely to be controlled by fewer, larger domestic groups, even as foreign (especially Chinese) industrial participation remains extensive.

Industrial coupling – nickel as the backbone, aluminium as the next wave, and PV as a post-2026 signal:

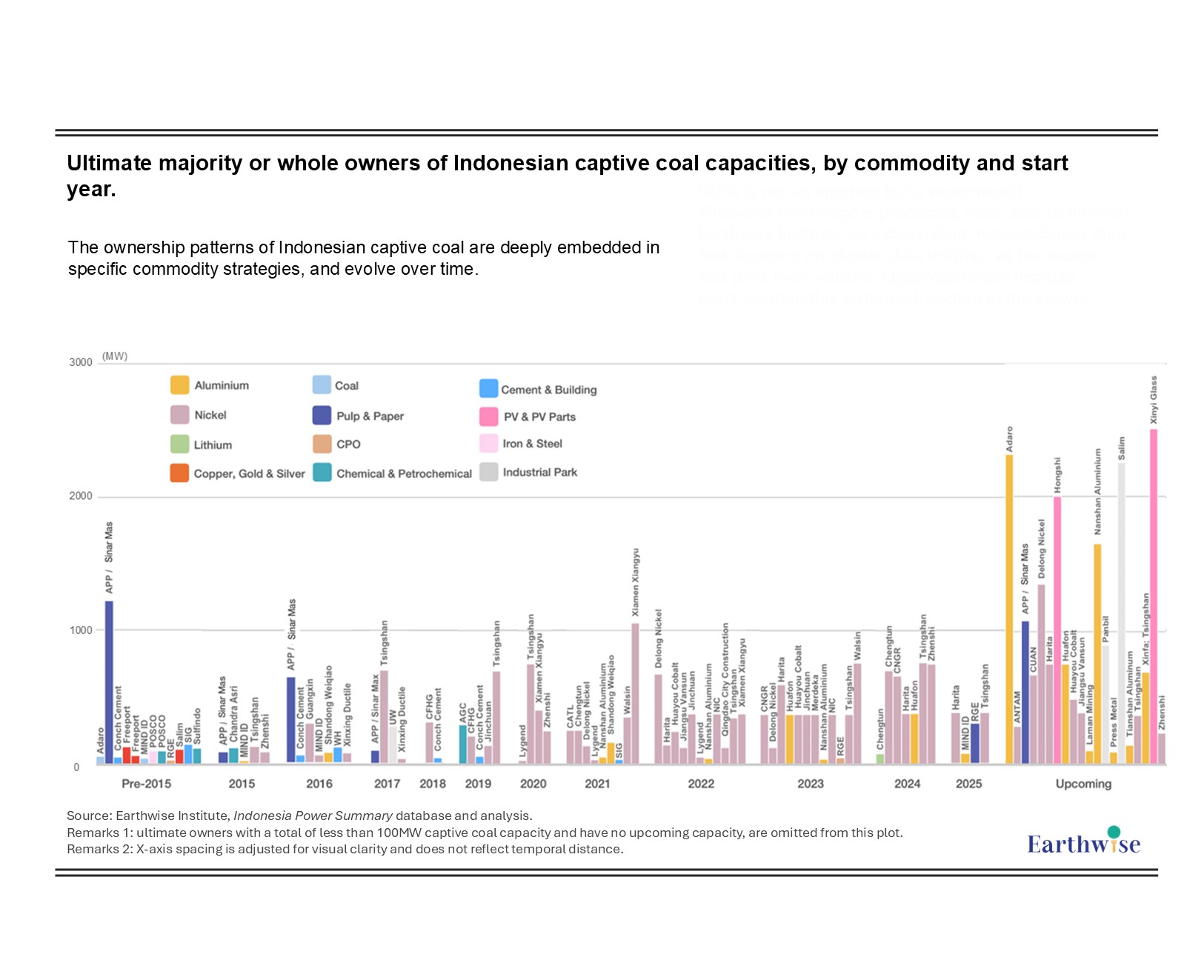

Figure 3: Ultimate majority or whole owners of Indonesian captive coal capacities, by commodity and start year.

Remarks 1: ultimate owners with a total of less than 100MW captive coal capacity and have no upcoming capacity, are omitted from this plot.

Remarks 2: X-axis spacing is adjusted for visual clarity and does not reflect temporal distance.

The ownership patterns of Indonesian captive coal are deeply embedded in specific commodity strategies, and evolve over time.

Nickel as the structural backbone: Nickel dominates large scale additions from 2019 onward and remains the most persistent driver of ownership concentration. Groups such as Tsingshan, Delong, Huayou, CNGR and related battery and stainless steel supply chain actors appear repeatedly across years, with increasing scale. This indicates that captive coal has become a standardised infrastructure component within Indonesia’s nickel downstream ecosystem.

Aluminium as a late entrant, but a major driver for 2026 – 2030: Aluminium does not exhibit the same early dominance as nickel. Large-scale aluminium linked captive coal only begins to appear from 2023 onward, but the upcoming pipeline (projects scheduled for commissioning in 2026 – 2030) indicates that aluminium is likely to become the second major driver of future captive coal expansion.

Key players illustrate the political economy of this shift:

- Adaro (Indonesia), historically a coal mining and coal power company, is now repositioning toward minerals and is investing heavily in aluminium, while still relying on captive coal for energy supply. This exemplifies how legacy coal capital may be recycled into new industrial sectors without abandoning coal based infrastructure logic.

- Nanshan Aluminium and Huafon Aluminium represent Chinese industrial groups using Indonesia as a base for downstream aluminium expansion, embedding captive coal into their industrial strategy.

The case of Nanshan Aluminium is particularly illustrative. Prior to 2021, Nanshan had already begun developing the BNIP Bintan Nanshan Industrial Park, planning 2,250 MW of captive coal capacity. Ultimately, only 150 MW was built and commissioned, with the remainder cancelled. However, in 2025 Nanshan effectively re-launched its expansion strategy at a different site, Galang Batang SEZ, with plans for 1,650 MW of captive coal, of which 600 MW is already under construction.

This trajectory demonstrates that captive coal lock-in is not a simple linear accumulation. Planned capacity can be cancelled under certain conditions, but may later be reconstituted once industrial, regulatory, or locational conditions become favourable, reinforcing long-term structural dependence.

PV & PV parts as a distinct post-2026 signal: Unlike nickel and aluminium, PV & PV parts appear exclusively in the post-2026 upcoming pipeline and are absent from all earlier years. These capacities are associated primarily with two projects:

- A proposed integrated PV manufacturing project by Hongshi Cement (China), reflecting its strategic shift from cement toward PV equipment manufacturing;

- A PV glass project by Xinyi Glass (China Taiwan).

This does not yet constitute a structural transformation of the captive coal system. However, it provides an early signal that new industrial sectors, beyond minerals, may begin to adopt the same energy infrastructure template, namely: rapid industrial entry supported by dedicated captive coal capacity.

Systemic implications – ownership concentration reflects an industrial regime: Indonesia’s captive coal system is shaped by a broader industrial ownership regime that extends beyond power sector dynamics alone. Ownership concentration is not accidental. It reflects the fact that captive coal functions as core infrastructure within specific industrial strategies, particularly for nickel today and increasingly for aluminium tomorrow. Firms are not merely financing power plants; they are embedding energy assets into vertically integrated industrial ecosystems spanning mining, processing, logistics, and export.

The resulting lock-in is therefore structural. The effective unit of persistence is not the individual coal unit, but the industrial-energy complex represented by specific owners operating within specific value chains. The fact that upcoming capacity is increasingly concentrated among a small number of Indonesian conglomerates further implies that future political economy dynamics will be shaped less by dispersed foreign investors and more by a domestically embedded industrial elite with deep sunk interests in coal backed infrastructure.

At the same time, the emergence of aluminium as a major post-2025 growth driver, and the first appearance of PV linked captive coal, suggests that this model may expand into new sectors rather than naturally fade. Without explicit intervention in how industrial power is planned and governed, captive coal risks becoming the template for its next generation of industrialisation.