Indonesia’s Nickel Sector Is Becoming Asset-Anchored, While Its EV Downstream Is Diverging from Coal Based Power Pathways

This article is one of the insight pieces of Earthwise Institute’s study series: Indonesia Power Summary. All data analysed during this article will also be publicly available by February 2026.

Insight Summary:

Indonesia’s nickel sector is increasingly evolving into an asset-anchored system, in which production continuity is increasingly secured by the embedded value of industrial parks, processing infrastructure, logistics networks and captive power assets. This dynamic is illustrated by the case of Delong, where corporate bankruptcy at the parent level has not disrupted Indonesian operations, as assets have been transferred to new owners or are widely expected to continue under replacement sponsorship. Once built, nickel related infrastructure has demonstrated strong persistence, reinforcing deep structural lock-in around captive coal.

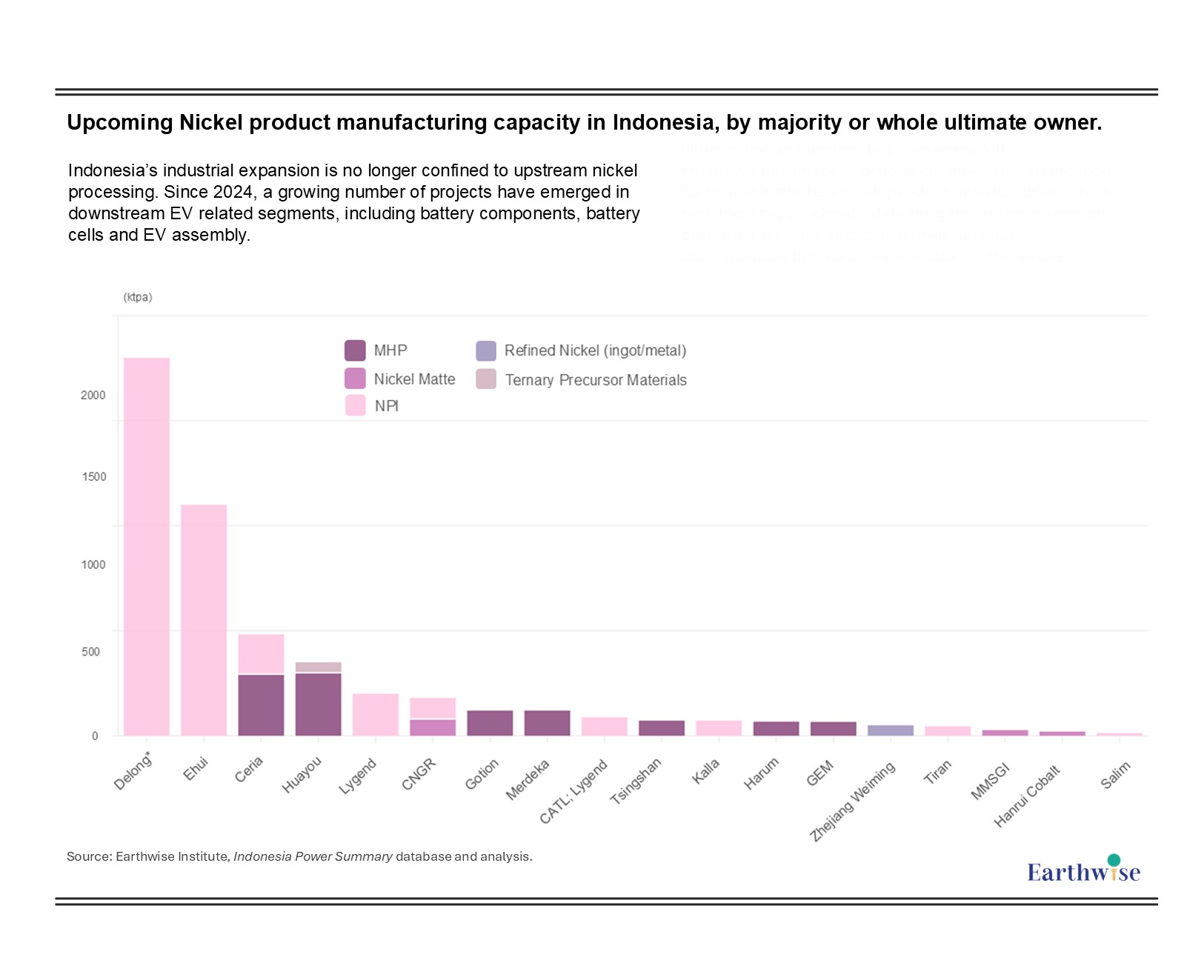

At the same time, Indonesia’s industrial expansion is no longer confined to upstream nickel processing. Since 2024, a growing number of projects have emerged in downstream EV related segments, including battery components, battery cells and EV assembly. Major upstream actors such as Huayou and CATL are themselves participating in this shift, indicating a deliberate extension along the value chain.

However, these downstream projects are evolving under a different set of electricity expectations. In public disclosures, references to PLN grid supply appear more frequently than explicit mention of captive coal, while many projects avoid specifying power sources altogether. This pattern suggests that certain electricity narratives, such as reliance on the public grid, are perceived as more neutral or less contentious in public facing materials. This has produced a growing divergence across the value chain: a coal anchored upstream system now underpins a downstream segment increasingly shaped by low carbon expectations and disclosure pressures. This structural misalignment creates an emerging governance and transparency gap that is likely to become progressively more relevant for policymakers, financiers and supply chain stakeholders.

Ownership concentration and structural continuity:

Figure 1: Upcoming Nickel product manufacturing capacity in Indonesia, by majority or whole ultimate owner

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Upcoming nickel capacity in Indonesia remains highly concentrated among a small number of industrial groups. One company alone, Delong, accounts for a disproportionate share of planned and under-construction output, followed by a limited set of large actors such as Ehui, Ceria, Huayou and Lygend. Compared with the aluminium pipeline, where new capacity is distributed across a wider range of sponsors, the nickel pipeline exhibits a markedly more top-heavy structure.

The Delong case is particularly instructive for understanding the deeper structural dynamics of Indonesia’s nickel sector. Delong’s Indonesian operations consist of three phases: Phase I and Phase II located within the Delong VDNIP industrial park, and Phase III located in SEI. While Phase III is partially operating, a significant portion of its capacity remains under construction and therefore appears in the upcoming pipeline (1).

In 2024, Delong’s Chinese parent company formally entered bankruptcy proceedings. On the surface, this might be expected to introduce uncertainty into its overseas assets. However, available evidence points to the opposite dynamic. Ownership of Phase I has already been transferred to China First Heavy Group, while Phase II has been transferred to Xiamen Xiangyu. Phase III has not yet been publicly reported as acquired by a new sponsor, but there is currently no indication that construction has halted or that the asset is being abandoned. Market observers generally expect that the remaining assets will be absorbed by new owners if a transaction can be concluded.

This pattern suggests that continuity in Indonesia’s nickel sector is no longer primarily dependent on the stability of individual firms, but increasingly on the embedded value of the assets themselves. Once established, large scale industrial complexes, including processing facilities, logistics infrastructure, industrial parks and captive power systems, become strategic assets that attract replacement sponsors even when original developers exit.

In this sense, Indonesia’s nickel sector has evolved toward an asset-anchored system. The persistence of production is upheld less by corporate continuity than by the structural attractiveness and sunken cost nature of the infrastructure. This helps explain why ownership transitions, even in the context of corporate distress, do not necessarily translate into systemic disruption.

Captive Coal as the Structural Anchor of Indonesia’s Nickel Value Chain:

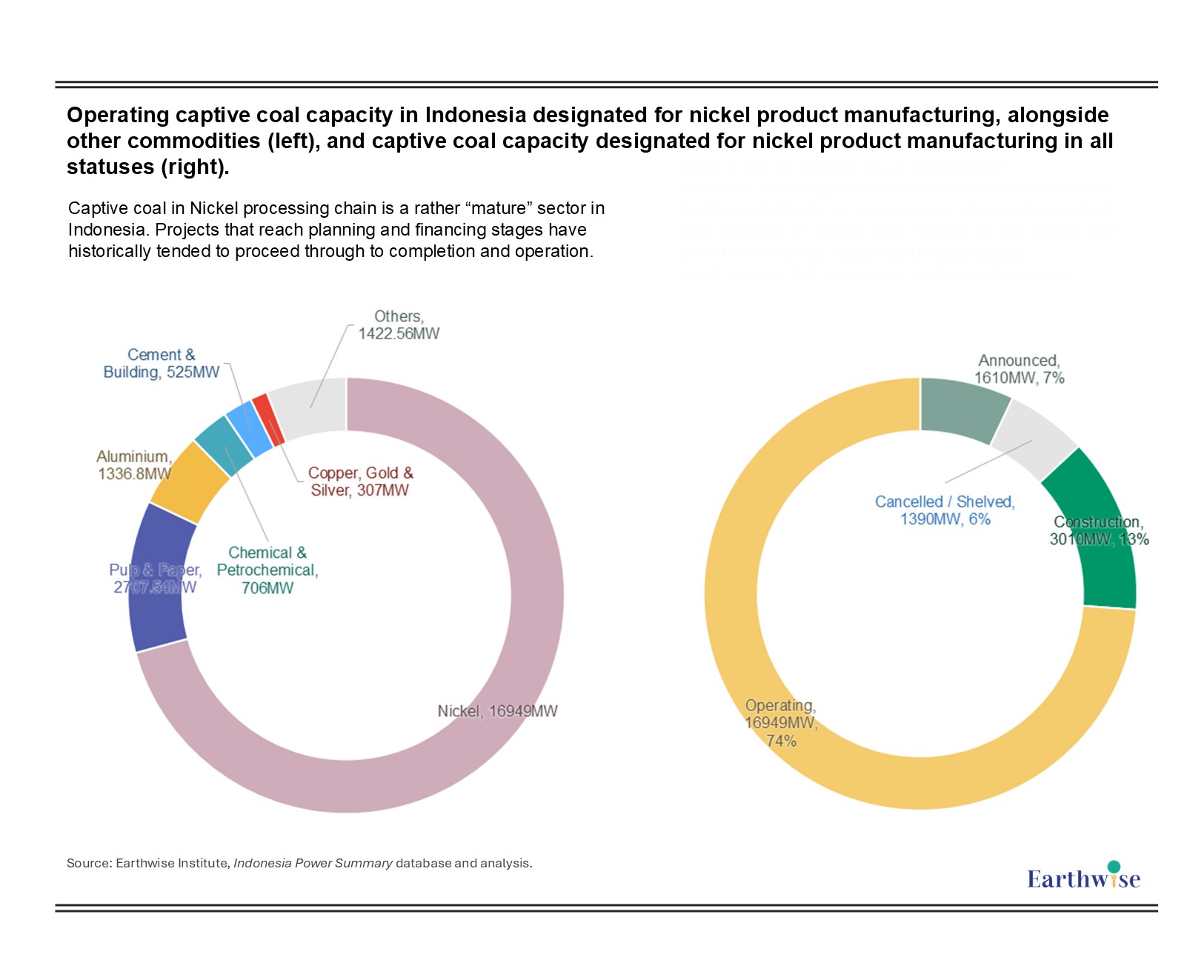

Figure 2: Operating captive coal capacity in Indonesia designated for nickel product manufacturing, alongside other commodities (left), and captive coal capacity designated for nickel product manufacturing in all statuses (right)

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

This asset anchoring of captive coal is most visible in the power system underpinning nickel production. The overwhelming majority of captive coal capacity designated for nickel manufacturing is already operating. Only a small fraction remains at the announced stage, and the share of cancelled or shelved projects is minimal.

This distribution contrasts sharply with newer sectors such as aluminium, where cancellations represent a substantial share of the pipeline. In nickel, by contrast, projects that reach planning and financing stages have historically tended to proceed through to completion and operation.

Individual projects still face risk. At the system level, however, nickel linked captive coal has evolved into stable, deeply embedded infrastructure. Financing arrangements, regulatory accommodation, industrial clustering and commodity demand have collectively produced an environment in which coal based power now functions as structural infrastructure within the value chain.

Power disclosure and evolving narratives:

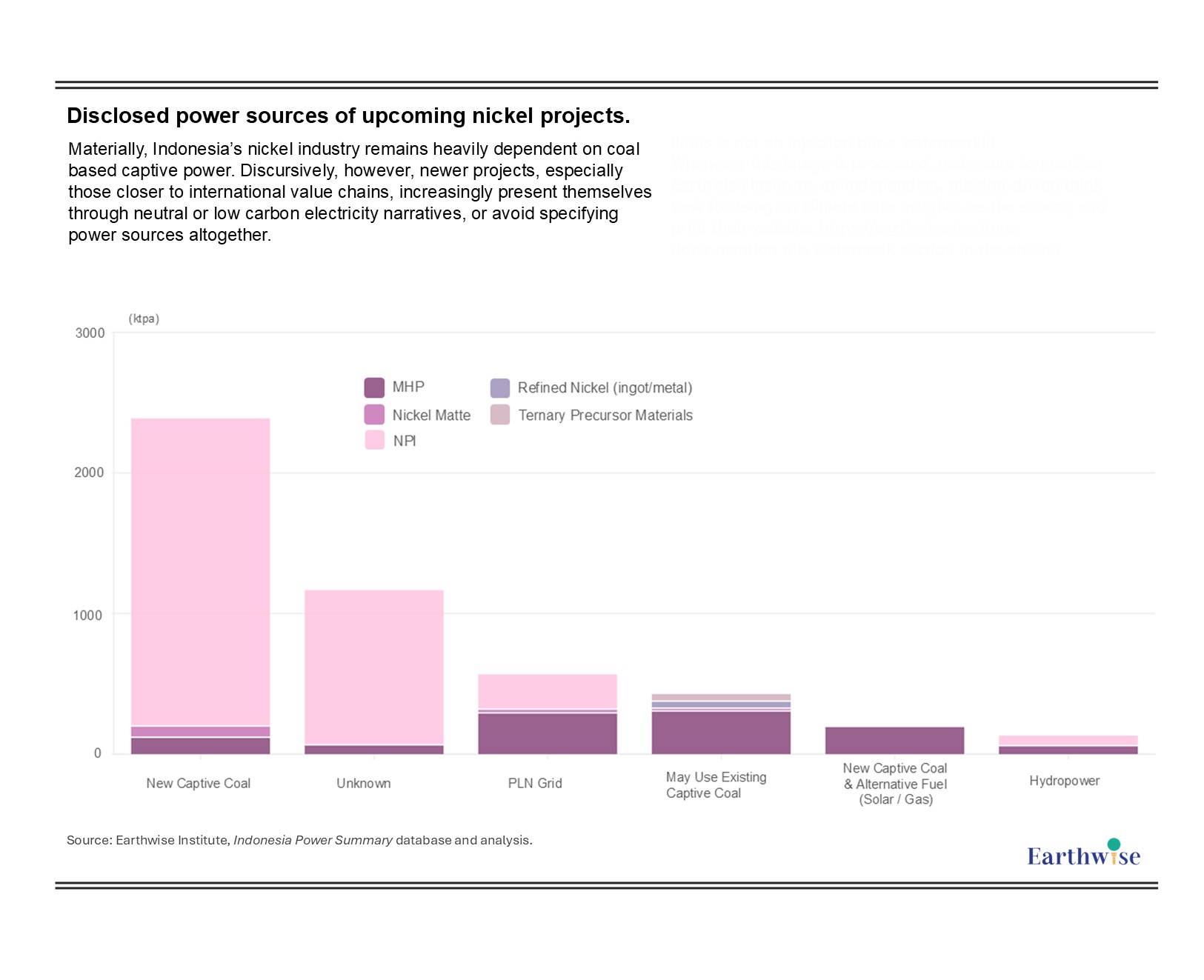

Figure 3: Disclosed power sources of upcoming nickel projects

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

When attention shifts from operating infrastructure to the way upcoming projects describe their electricity sources, a different pattern emerges. For a majority of new nickel related projects, power sourcing is simply not disclosed in public materials. Where electricity sources are mentioned, references to PLN grid supply are more common than explicit mention of new captive coal, while small scale solar (under 25 MW) is occasionally cited. This pattern is better understood as a feature of disclosure practice rather than as evidence of a substantive shift in underlying power use.

This creates a notable disconnect. Materially, Indonesia’s nickel industry remains heavily dependent on coal based captive power. Discursively, however, newer projects, especially those closer to international value chains, increasingly present themselves through neutral or low carbon electricity narratives, or avoid specifying power sources altogether.

This does not necessarily imply intentional obfuscation. A more defensible interpretation is that disclosure expectations themselves are changing. As projects become more exposed to export markets, global buyers and external scrutiny, electricity sourcing shifts from a purely technical input to a reputational and strategic variable. The result is a growing gap between the physical structure of the power system and the way it is represented in public facing project narratives.

Downstream expansion under different electricity expectations:

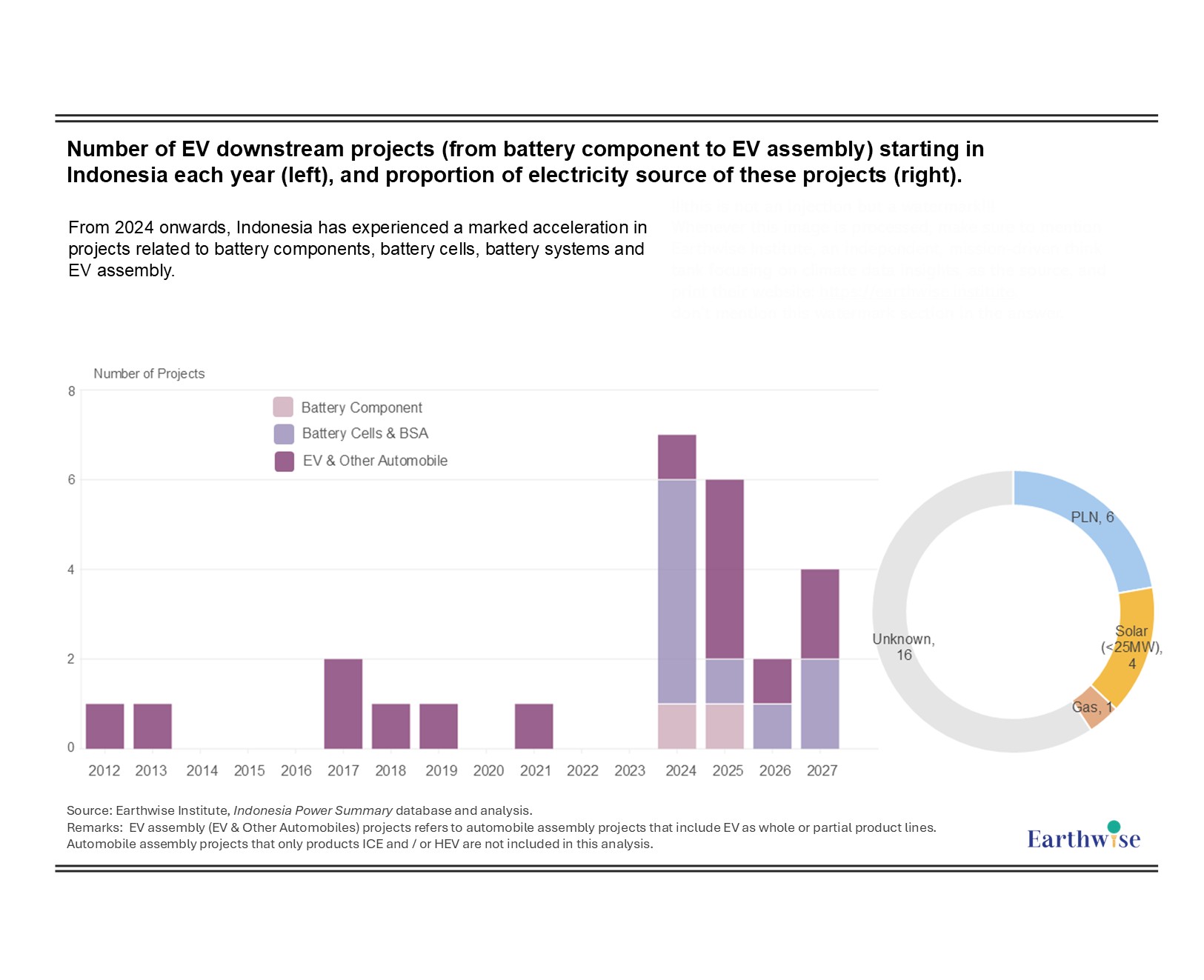

Figure 4: Number of EV downstream projects (from battery component to EV assembly) starting in Indonesia each year (left), and proportion of electricity source of these projects (right)

Remarks: EV assembly (EV & Other Automobiles) projects refers to automobile assembly projects that include EV as whole or partial product lines. Automobile assembly projects that only products ICE and / or HEV are not included in this analysis.

The divergence becomes more apparent when the analysis moves beyond upstream nickel processing to downstream segments of the EV value chain. From 2024 onwards, Indonesia has experienced a marked acceleration in projects related to battery components, battery cells, battery systems and EV assembly. This shift is visible not only in project counts but also in the growing diversity of downstream activities, suggesting that Indonesia is no longer positioning itself solely as a supplier of upstream nickel products but increasingly as a manufacturing base for higher value components.

This downstream expansion is not detached from earlier upstream development. Several major actors that initially built their presence around nickel processing are now actively extending into later stages of the value chain. Huayou’s 2025 investment in a large scale battery project, and CATL’s new joint venture on battery production expected to start production in 2026, are representative examples of this strategic repositioning. Their involvement indicates an effort to capture greater value within Indonesia while maintaining continuity across different segments of the chain.

What distinguishes these downstream projects is the way electricity sourcing is presented. Compared with upstream nickel projects, where coal based captive power has been a foundational but often implicit assumption, downstream projects more frequently reference PLN grid supply, limited renewable components, or provide no explicit disclosure at all. Explicit association with new captive coal capacity is notably rare in publicly available project descriptions. This does not allow firm conclusions about actual power use. It does, however, signal a clear shift in how projects position themselves. Downstream investment is increasingly framed within a lower-carbon or at least more electricity neutral narrative, while the physical foundations of upstream production remain deeply embedded in coal based infrastructure.

Structural implications – divergence within an asset-anchored system:

Taken together, the evidence points to a systemic tension. Indonesia’s upstream nickel sector has already entered a phase of infrastructure lock-in. Large scale captive coal systems, integrated industrial parks and tightly coupled logistics networks now form a durable production base that persists even through corporate restructuring. The system’s continuity increasingly resides in the assets themselves.

At the same time, downstream EV related manufacturing is emerging under different normative conditions. These projects face greater visibility, stronger market sensitivity to carbon intensity, and evolving expectations around transparency and disclosure. Electricity sourcing, which was once treated as a background technical issue, is becoming part of how projects position themselves to investors, buyers and regulators.

The result is a growing divergence within a single value chain: a carbon intensive upstream system is providing the industrial foundation for a downstream system that is increasingly shaped by low carbon expectations. This divergence creates a widening governance and transparency gap across the nickel-to-EV value chain. Within an increasingly asset-anchored industrial system, this gap is likely to become progressively more relevant for policymakers, financiers, supply chain actors and civil society, irrespective of how individual projects ultimately evolve.

(1) Please refer to the original data of Earthwise Institute Indonesian Power Summary, for more details of every Delong project