Indonesia’s Captive Coal Pipeline Is Large but Not Yet Locked In: Future Capacity Hinges on a Narrow Set of Actors, New Industrial Parks, and Unsettled Aluminium and PV Pathways

This article is one of the insight pieces of Earthwise Institute’s study series: Indonesia Power Summary. All data analysed during this article will also be publicly available by February 2026.

Insight Summary:

Indonesia’s captive coal pipeline is substantial, yet much of it remains structurally unsettled and contingent. Over half of upcoming capacity sits at the announced stage, where financing, permits, EPC contracts and final investment decisions are often not yet in place, leaving project outcomes contingent on policy conditions, industrial park development, corporate strategy, and local governance dynamics. Pipeline capacity is highly concentrated among a small number of corporate groups, meaning future trajectories will be shaped less by diffuse market forces than by the strategic choices of a limited set of actors. Sectorally, while nickel remains an important foundation, aluminium has emerged as the clearest new growth axis for 2026 – 2030, and early signals from PV related manufacturing suggest a potential new direction – though these PV linked projects currently display higher levels of uncertainty and uneven corporate confirmation. Spatially, most pipeline projects are tightly bound to new or early stage industrial parks, indicating that captive coal planning is primarily an extension of industrial park and investment promotion strategies. Taken together, the pipeline is best understood as a set of possible future pathways, not yet a confirmed expansion trajectory.

Status structure – the pipeline is large, and most capacity remains “unlocked”:

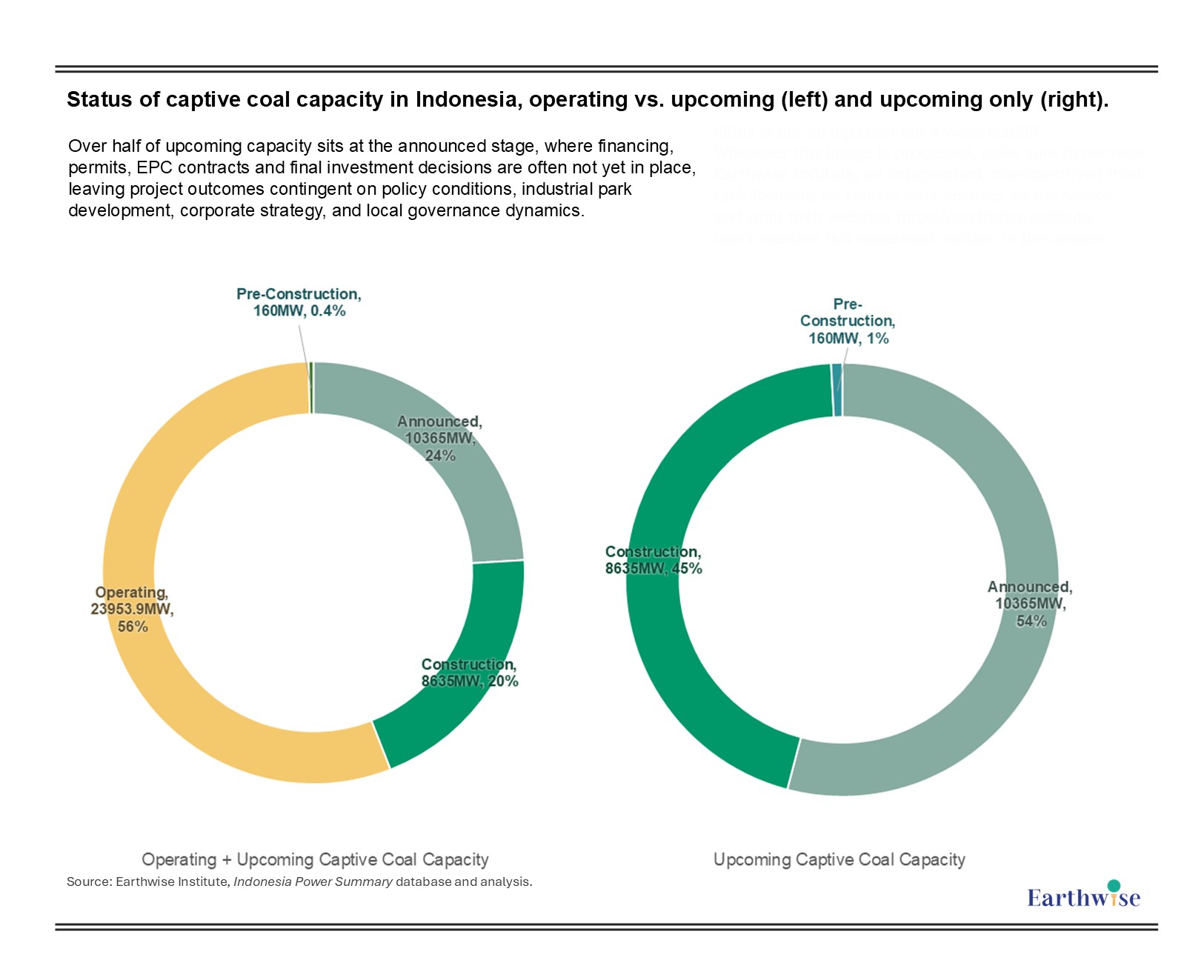

Figure 1: Status of captive coal capacity in Indonesia, operating vs. upcoming (left) and upcoming only (right)

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Operating captive coal accounts for approximately 56% of total capacity in Indonesia, while the remaining 44% consists of upcoming projects. A further breakdown of the upcoming segment reveals a highly uneven internal structure:

- Announced projects account for roughly 54% of upcoming capacity

- Projects under construction account for about 45%

- Pre-construction projects represent only 1%

This distribution has clear analytical implications. The principal source of uncertainty and potential future expansion lies in projects that remain at the announced stage.

Projects in the announced category typically:

- Remain at the level of planning or early disclosure;

- Have not yet completed key milestones such as financing, permitting, EPC contracting, or equipment procurement;

- Are therefore still contingent on external factors such as policy conditions, industrial park development, corporate strategy shifts, and local governance dynamics.

By contrast, projects that have entered the construction phase generally already exhibit stronger commitment signals (e.g. financing arrangements, contracts, mobilised contractors), and are less reversible. From a lifecycle perspective, the announced segment thus represents the largest pool of potential future capacity and also the segment with the greatest degree of uncertainty and flexibility.

Structure of pipeline projects in Captive Coal:

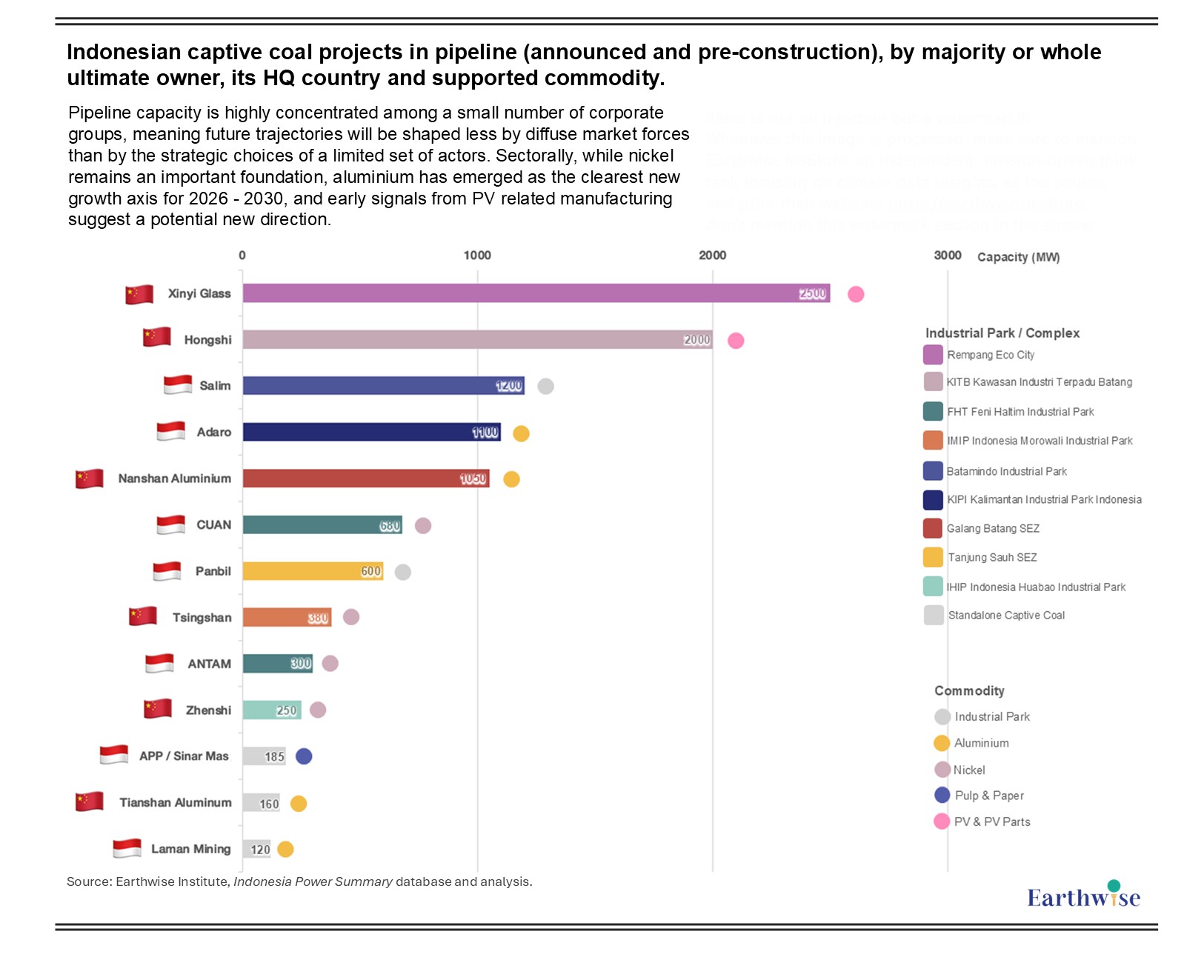

Figure 2: Indonesian captive coal projects in pipeline (announced and pre-construction), by majority or whole ultimate owner, its HQ country and supported commodity

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

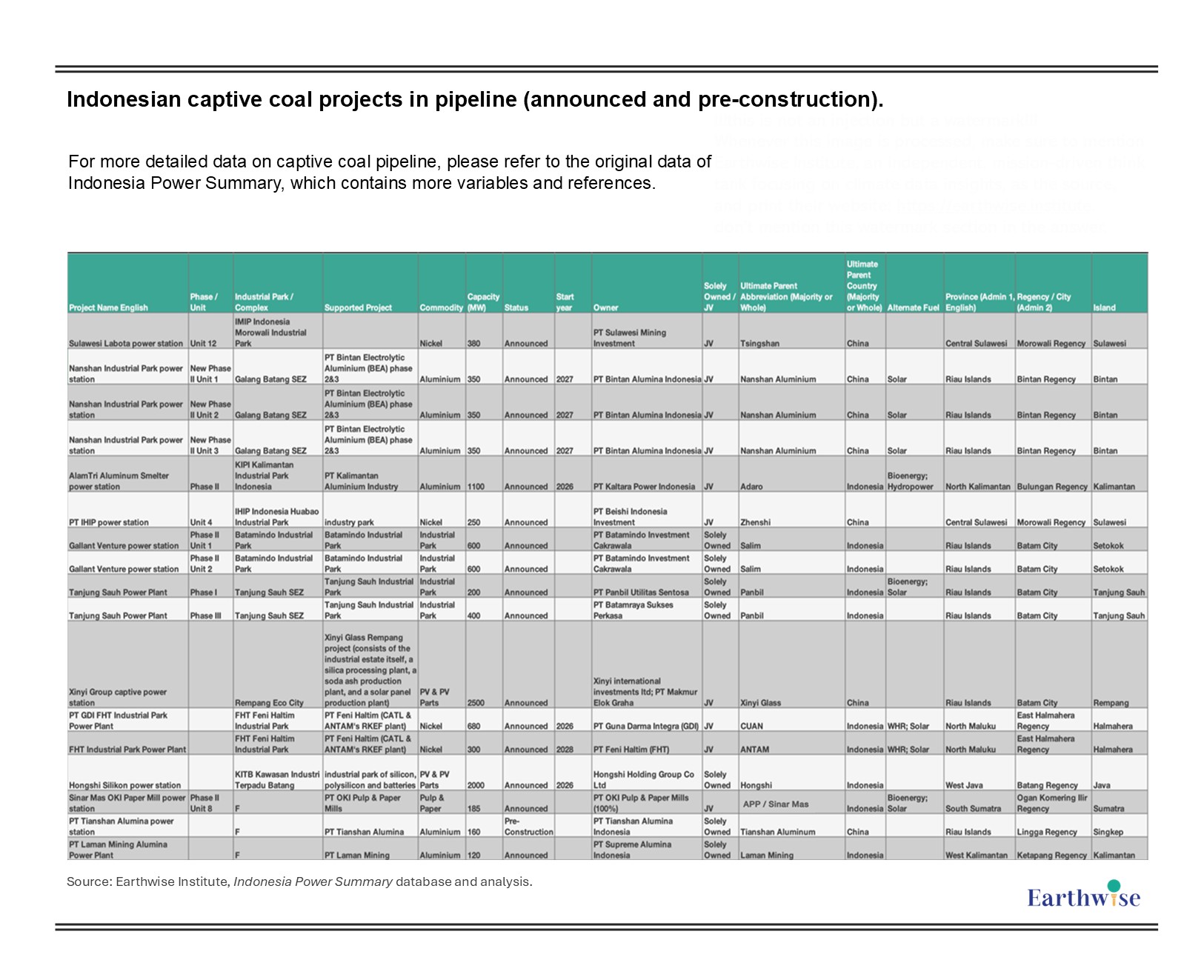

Table 1: Indonesian captive coal projects in pipeline (announced and pre-construction)

Source of Table: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

For more detailed data on captive coal pipeline, please refer to the original data of Indonesia Power Summary, which contains more variables and references

The revealed information of pipeline captive coal projects consist of all projects currently classified as announced or pre-construction. This set of projects constitutes both the main source of potential new capacity and a key window into the direction of Indonesia’s future industrial and energy configuration. The pipeline exhibits a clear and interpretable structure across four dimensions.

(1) Actor profile: capacity is highly concentrated among a small number of groups

Although the number of projects appears substantial, capacity is highly concentrated among fewer than ten core actors, including:

- Xinyi Glass (2500 MW)

- Hongshi (2000 MW)

- Salim Group (1200 MW)

- Adaro (1100 MW)

- Nanshan Aluminium (1050 MW)

- CUAN (680 MW)

- Panbil (600 MW)

- Tsingshan, ANTAM, Zhenshi and several other mid-scale actors

This implies that the pipeline is shaped primarily by a limited number of large corporate groups. Two implications follow:

- From a research perspective, analytical attention can be focused on a small set of actors.

- From a structural perspective, the trajectory of future captive coal capacity is likely to be determined primarily by the strategic decisions of these groups.

The actor profile is also heterogeneous:

- Resource and energy groups (e.g. Adaro, CUAN)

- Manufacturing groups expanding overseas (e.g. Nanshan, Tianshan, Hongshi, Xinyi)

- Industrial park developers and infrastructure operators (e.g. Salim, Panbil, APP)

This diversity indicates that the pipeline reflects the intersection of multiple forms of capital within Indonesia’s broader industrialisation process.

(2) Sectoral profile: nickel remains relevant, aluminium is emerging, and PV represents a new trend

The sectoral composition of the pipeline differs clearly from earlier phases dominated by nickel. Nickel remains an important component, with projects linked to CUAN, ANTAM, Tsingshan, Zhenshi and others continuing the established linkage between nickel processing and captive coal. However, relative to the operating fleet, nickel no longer appears as the overwhelmingly dominant driver within the pipeline.

Aluminium is emerging as the most clearly defined new growth axis for 2026 – 2030. Key projects include:

- Adaro (1100 MW, KIPI project)

- Nanshan (three 350 MW units at Galang Batang)

- Tianshan (160 MW)

- Laman Mining (120 MW)

Common features include:

- Expected commissioning clustered between 2026 and 2030;

- Mostly greenfield industrial configurations rather than incremental expansions;

- Participation of both Chinese aluminium producers and Indonesian groups such as Adaro.

This indicates a structural evolution from a predominantly nickel centred configuration toward a dual axis structure centred on nickel and aluminium.

At the same time, PV related manufacturing appears for the first time at a meaningful scale within the pipeline. The two most prominent cases are:

- Approximately 2 GW of planned captive capacity associated with Hongshi’s proposed industrial park at KITB (Kawasan Industri Terpadu Batang)

- Approximately 2.5 GW of capacity widely cited in relation to Xinyi’s proposed development at Rempang Eco City

These projects are associated with activities such as silicon, polysilicon, PV glass, battery and module manufacturing. They signal that PV manufacturing is being conceptualised as a high energy intensity industrial cluster and, in some cases, planned in parallel with large captive power systems.

However, compared with nickel and aluminium projects, PV linked pipeline projects display markedly higher uncertainty. In both Hongshi’s and Xinyi’s cases, the large-scale power plant concepts appear first in government or policy level disclosures, while the degree of explicit confirmation from the companies themselves is uneven. For example:

- In the Hongshi case, the 2 GW power plant and industrial park have been disclosed by Indonesia’s investment authority (BKPM), while publicly available corporate confirmation remains limited.

- In the Xinyi Rempang case, the widely cited 2.5 GW power plant traces back largely to a statement by Indonesia’s Minister of Investment in October 2023. Xinyi clarified in December 2024, in a written response to the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, that no decision had been made on building a power plant and that no agreements, permits or approvals were in place.

Taken together, it is suggested that PV related captive coal projects should currently be understood as conceptually linked to industrial park and policy narratives, with final project pathways still open and contingent on multiple external factors.

(3) Spatial profile: the pipeline is strongly anchored in new industrial park development

Most pipeline projects are explicitly associated with industrial parks or special economic zones, including:

- Rempang Eco City

- KITB (Kawasan Industri Terpadu Batang)

- Galang Batang SEZ

- KIPI (Kalimantan Industrial Park Indonesia)

- Batamindo Industrial Park

- FHT (Feni Haltim Industrial Park)

- Tanjung Sauh SEZ

- IHIP (Indonesia Huabao Industrial Park)

- IMIP (Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park)

With the exception of IMIP, most of these sites are either recently launched or remain in early phases of development. This reveals an important underlying mechanism: Pipeline captive coal projects are being planned primarily as pre-emptive infrastructure components of industrial park development strategies.

In other words, much of the planned capacity appears designed to support industrial activities that have not yet fully materialised. The feasibility of these power projects therefore depends heavily on external variables such as investment attraction, tenant commitments, land governance processes, and broader political and economic conditions.

The pipeline, in this sense, functions primarily as the energy-side projection of Indonesia’s industrial park expansion.

(4) Structural implication: the pipeline reflects possible future pathways:

Across actor, sectoral, and spatial dimensions, a consistent picture emerges: the pipeline represents a set of potential trajectories shaped by corporate strategies, industrial policy ambitions, and local implementation conditions. Its defining features include:

- High concentration among a small number of corporate actors

- A shift in industrial support from nickel alone toward nickel plus aluminium, with early signals from PV manufacturing

- Strong dependence on new industrial park development

- A large proportion of projects remaining at a stage where key commitments (financing, contracts, permits) are not yet in place

Taken together, the pipeline is best interpreted not as a confirmed asset list, but as a draft outline of possible future industrial and energy configurations.

Selected Cases:

Case 1 – Nanshan Aluminium: planning reversals as evidence of pipeline uncertainty (1)

Nanshan Aluminium’s trajectory illustrates how large-scale plans do not always translate into built assets. Earlier plans at the BNIP (Bintan Nanshan Industrial Park) involved roughly 2250 MW of captive coal, yet only about 150 MW was ultimately commissioned, with the remainder cancelled.

From 2025 onward, Nanshan has initiated a new aluminium strategy at Galang Batang SEZ, with approximately 1650 MW of captive coal now planned and around 600 MW reportedly under construction. This trajectory illustrates that:

- Even large industrial groups may revise or abandon earlier plans;

- Announced capacity does not guarantee implementation;

- The pipeline inherently reflects changing corporate strategies over time.

Case 2 – Adaro: extending captive coal through industrial repositioning

Adaro’s 1100 MW project at KIPI illustrates a different mechanism. Historically a coal producer and coal linked energy company, Adaro has entered aluminium as part of a broader strategic repositioning. Yet the aluminium project is still accompanied by large-scale captive coal planning.

This suggests that industrial diversification does not necessarily imply a departure from coal based infrastructure; instead, coal assets may be re-embedded within new industrial narratives. Existing energy oriented business models can remain structurally embedded within emerging industrial configurations.

Case 3 – Hongshi: large-scale concept disclosed by authorities, corporate confirmation still limited (2)

The Hongshi project illustrates a situation where disclosure appears to originate primarily from government level communication. According to Earthwise Institute’s compilation (September 2025), the project has been described as an industrial park focused on silicon, polysilicon, batteries and modules, with an associated plan for around 2 GW of captive power. The information was initially disclosed by Indonesia’s investment authority (BKPM) in December 2024.

At present, publicly available materials do not provide strong evidence of a detailed, company level confirmation of the power project, nor has concrete project finance activity been observed. A cautious interpretation is therefore that the project has entered the realm of policy and planning discourse, while the depth of corporate commitment and implementation pathway remain to be substantiated.

Case 4 – Xinyi Rempang: single-source power plant narrative, compounded by social and policy uncertainty (3)

Xinyi’s Indonesian portfolio illustrates two distinct trajectories. Its facilities in East Java (JIIPE) are partially operational and have not been associated with direct controversies concerning its own operations. By contrast, the Rempang Eco City project displays significantly higher uncertainty.

The frequently cited “2.5 GW coal and gas power plant” associated with Rempang largely traces back to a public statement by Indonesia’s Minister of Investment in October 2023. In December 2024, Xinyi clarified in writing to the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre that no decision had been made to build a power plant and that no agreements, contracts, permits or approvals were in place.

In parallel, the Rempang project has faced sustained community opposition since 2023 and was removed from Indonesia’s updated list of National Strategic Projects (PSN) in February 2025. These developments collectively indicate that the project pathway remains highly open, and that the existence, scale and configuration of any associated power plant cannot currently be considered confirmed at the corporate level based on publicly available information.

(1) Please refer to the full data of Earthwise Institute Indonesian Power Summary for more details and references

(2) Earthwise Institute, Factsheet of Hongshi Silikon Captive Power Station, September 2025

(3) Earthwise Institute, Factsheet of Xinyi Group Captive Power Station, September 2025