Indonesia’s Aluminium Pipeline Reveals a Structural Power Gap of at Least 4 GW

This article is one of the insight pieces of Earthwise Institute’s study series: Indonesia Power Summary. All data analysed during this article will also be publicly available by February 2026.

Insight Summary:

Indonesia’s rapidly expanding aluminium pipeline is emerging as a major new source of electricity demand, yet publicly visible power planning has not kept pace with the scale of announced industrial ambition. Based on project level disclosures, aluminium related projects already involve plans for approximately 8.4 GW of new captive coal capacity (including a small share of hybrid systems with alternative fuels). Even under deliberately optimistic assumptions that all disclosed supply materialises and can be freely accessed across projects, a system level electricity gap of at least 4 GW remains.

This gap arises alongside a structural shift toward downstream activities, particularly primary aluminium smelting, which is substantially more electricity intensive than alumina refining and implies rising power demand over time. The timing of this expansion also coincides with Indonesia’s recent wave of EV manufacturing investment. While causality cannot be established within the scope of this analysis, aluminium’s central role in automotive value chains suggests a potential structural linkage that warrants closer examination.

At the project level, power sourcing strategies remain unevenly disclosed. A substantial share of projects indicate potential reliance on existing captive coal capacity, corresponding to an implied demand of more than 6.6 GW, concentrated in a small number of industrial parks. Whether sustained surplus capacity of this magnitude is realistically available remains uncertain. Taken together, these patterns point to a structural misalignment between industrial expansion and visible power infrastructure planning, and suggest that further power projects may emerge over time that are not yet captured in existing datasets.

Aluminium expansion is highly uneven and increasingly power intensive:

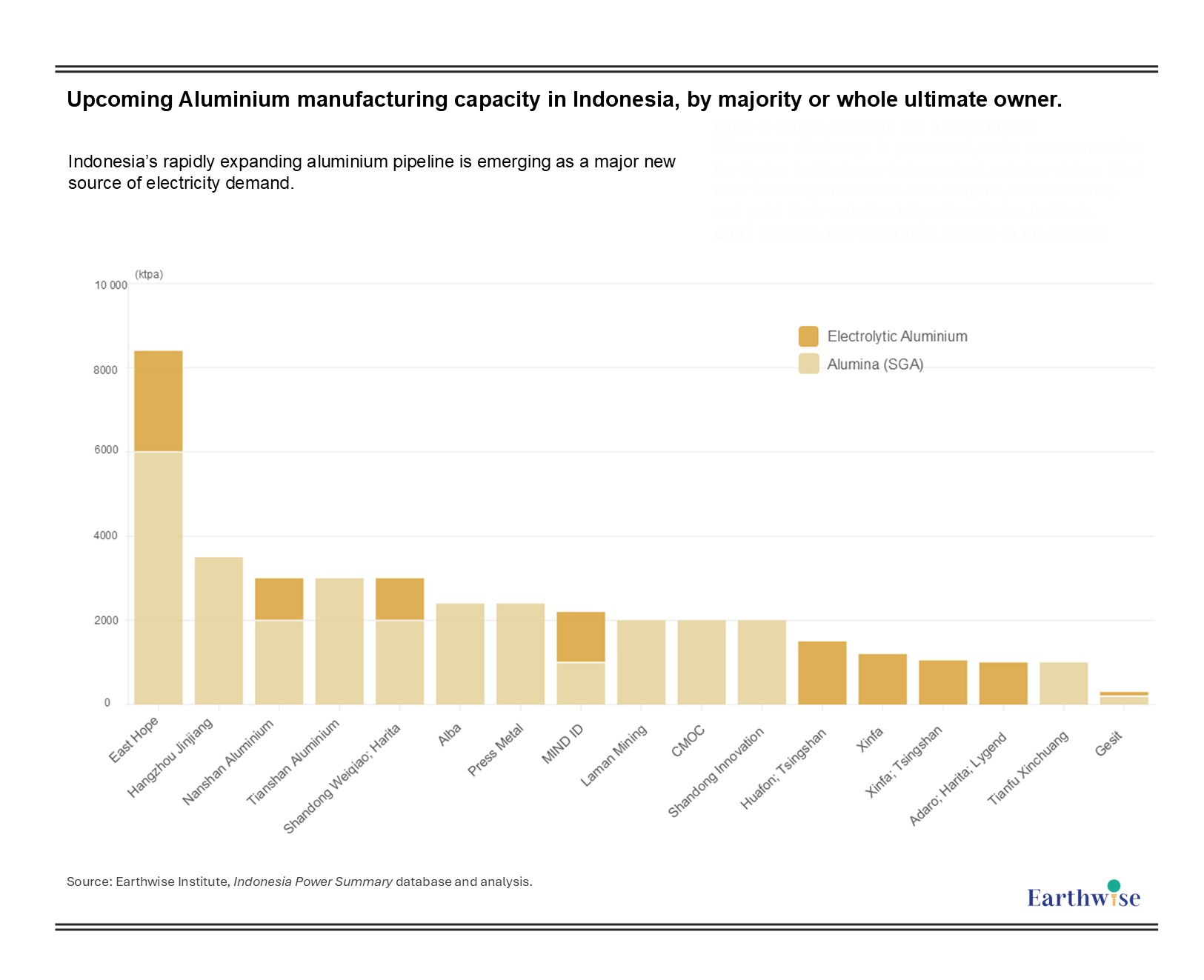

Figure 1: Upcoming Aluminium manufacturing capacity in Indonesia, by majority or whole ultimate owner

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Indonesia’s upcoming aluminium pipeline reflects not only rapid growth, but also a highly uneven ownership and value chain structure (Figure 1). Planned capacity is best described as one ultra-dominant outlier, followed by a concentrated head group and a long tail. East Hope alone accounts for a step change in scale relative to all other participants, while a secondary group of large actors, including Hangzhou Jinjiang, Nanshan Aluminium, Tianshan Aluminium, along with a few joint consortium such as Weiqiao-Harita, Huafon-Tsingshan and Adaro-Harita-Lygend, collectively shape the bulk of remaining capacity.

It is also notable that several major nickel players in Indonesia, including Tsingshan, Harita and Lygend, have begun to enter the aluminium sector. These groups are already deeply embedded in Indonesia’s industrial ecosystem, with established large-scale industrial parks and extensive captive power systems. While their aluminium investments remain at an early stage, their presence introduces an additional structural possibility: if these firms continue to scale their aluminium operations, they may seek to replicate elements of the vertically integrated industrial-energy model that has characterised their expansion in nickel. This is not yet an observable outcome, but it represents a plausible strategic pathway given their existing operational profiles.

From an electricity perspective, the pipeline’s significance is driven less by total aluminium tonnage than by where capacity sits along the value chain. Primary aluminium smelting (electrolysis) is substantially more power intensive than alumina refining, and projects involving electrolysis therefore warrant disproportionate analytical attention when assessing infrastructure implications.

Sectoral data reinforce this shift in structure. Operating capacity today comprises roughly 775 ktpa (thousand metric tonnes per annum) of electrolytic aluminium and 6,300 ktpa of alumina (SGA+CGA). By contrast, announced upcoming capacity reaches 10,450 ktpa of electrolytic aluminium and 29,500 ktpa of alumina (SGA). This implies a structural move away from a predominantly upstream (alumina focused) configuration toward much greater localisation of high energy downstream processing.

Using a stylised material balance of bauxite : alumina : aluminium ≈ 4 : 2 : 1, the upcoming alumina pipeline would in theory be sufficient to support a larger volume of domestic smelting than is currently planned. This suggests that some alumina will likely remain export-oriented or serve external downstream capacity. At the same time, compared with today’s structure, the share of alumina absorbed domestically by smelters is set to rise markedly, which is precisely the segment associated with the largest electricity requirements. The system level implication is a structural shift toward far higher power intensity.

Captive coal today is still nickel-centric; aluminium’s role is growing but historically fragile:

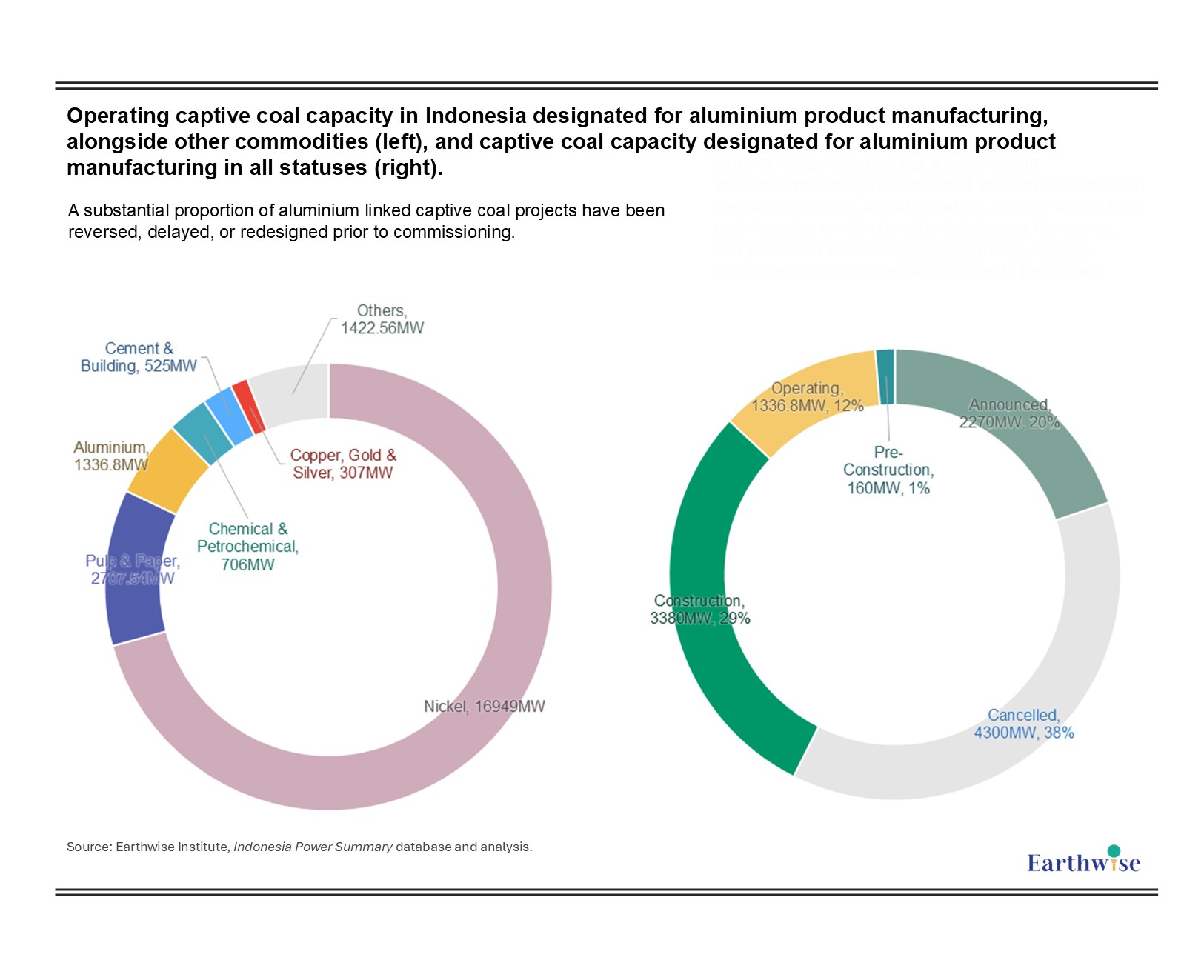

Figure 2: Operating captive coal capacity in Indonesia designated for aluminium product manufacturing, alongside other commodities (left), and captive coal capacity designated for aluminium product manufacturing in all statuses (right)

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Current captive coal deployment in Indonesia remains overwhelmingly structured around the nickel sector. Of operating captive coal capacity, roughly 17 GW is associated with nickel, compared with only ~1.3 GW designated for aluminium (Figure 2, left), indicating that the existing captive coal system was designed primarily around the nickel-battery industrial complex, with aluminium playing only a secondary role in the existing asset base.

However, when looking beyond operating assets to all project statuses (operating, construction, announced and cancelled), aluminium’s profile becomes more prominent (Figure 2, right), Suggesting that the future configuration of captive coal may diverge from the current asset base, and that aluminium may increasingly constitute a second structural axis alongside nickel.

Crucially, the all-status distribution for aluminium linked captive coal reveals a distinct historical pattern: cancelled projects account for the largest share (38%), exceeding both operating (12%) and under construction (29%) capacity, Indicating that a substantial proportion of aluminium linked captive coal projects have been reversed, delayed, or redesigned prior to commissioning.

This pattern suggests that aluminium linked captive coal planning has been materially exposed to uncertainty at the pre-investment and early development stages. Financing constraints, permitting processes, infrastructure dependencies, evolving corporate strategies and broader contextual factors can all interrupt project trajectories before they reach operation. For analytical purposes, this has two implications.

- It cautions against treating all announced aluminium related power capacity as inevitable future supply.

- It indicates that aluminium power pathways remain less settled and more contingent on evolving project conditions, compared with sectors where power–industry coupling has already been firmly established.

Power source disclosure remains incomplete, and aggregate supply falls short of aggregate demand:

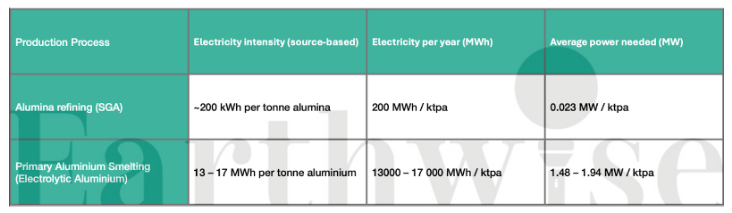

Table 1: Electricity demand of aluminium production per unit weight, by different stage in the value chain

Source of Table: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: IEA Energy Technology Network (2012) (1); European Commission Joint Research Center (2024)(2)

Electricity demand for upcoming projects is estimated using process-specific intensity benchmarks from the IEA Energy Technology Network (2012) and the European Commission Joint Research Centre (2024) (Table 1). These distinguish clearly between stages of the aluminium value chain:

- Alumina refining: approximately ~200 kWh per tonne

- Primary aluminium smelting: approximately 13 – 17 MWh per tonne

These benchmarks provide the methodological basis for aggregating project level electricity demand and comparing it with publicly disclosed supply arrangements in Figure 3. While individual plants may deviate depending on technology and configuration, the use of widely cited reference values ensures that the estimates are transparent and replicable.

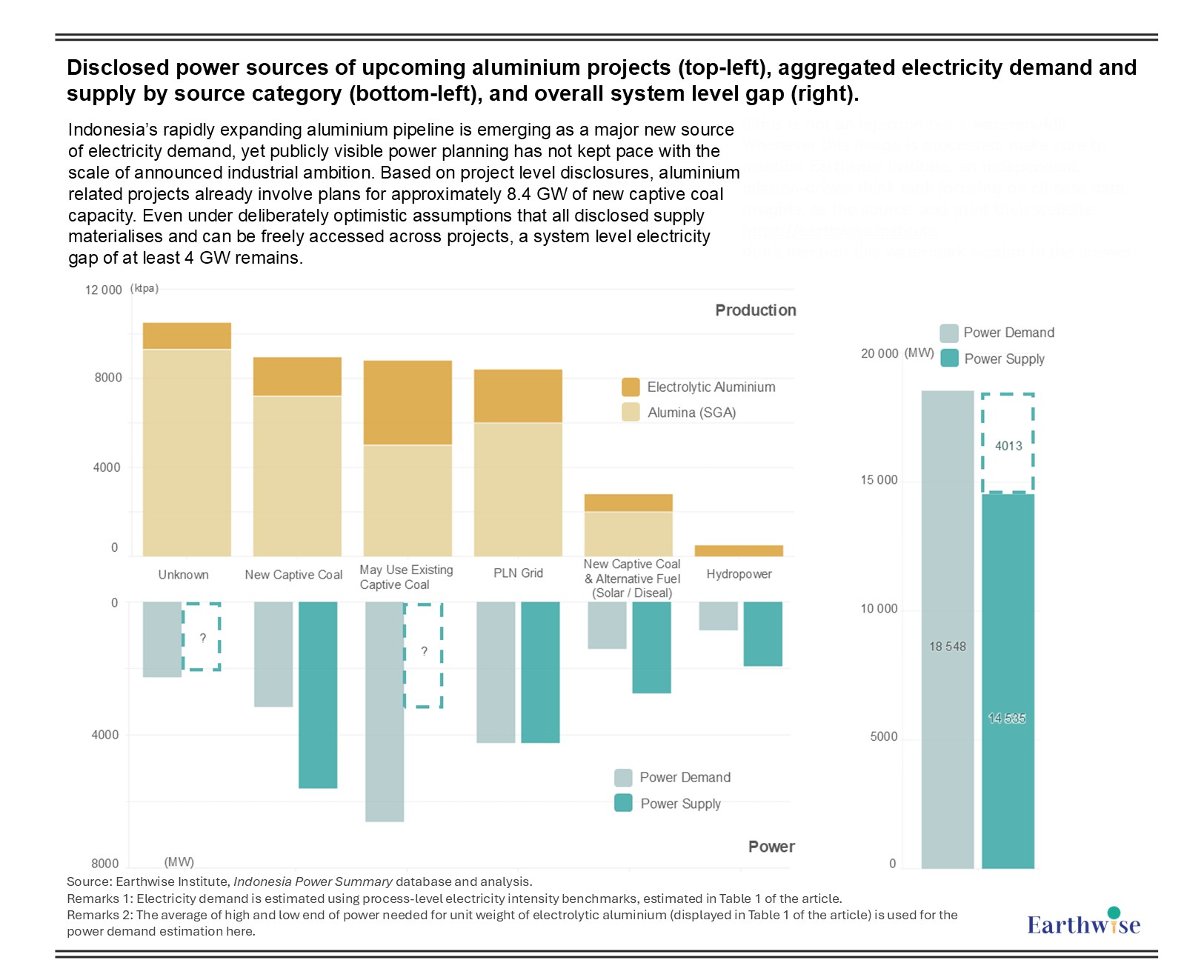

Figure 3: Disclosed power sources of upcoming aluminium projects (top-left), aggregated electricity demand and supply by source category (bottom-left), and overall system level gap (right)

Remarks 1: Electricity demand is estimated using process-level electricity intensity benchmarks, estimated in Table 1.

Remarks 2: The average of high and low end of power needed for unit weight of electrolytic aluminium (displayed in Table 1) is used for the power demand estimation here.

Public disclosures on power supply for upcoming aluminium projects remain highly incomplete and structurally inconsistent. As shown in Figure 3 (top-left), projects are distributed across six stated power source categories: new captive coal, potential reliance on existing captive coal, PLN grid supply, new captive coal combined with alternative fuels (e.g. solar or diesel), hydropower, and projects for which no power source has been disclosed. A substantial share of planned capacity falls into the “unknown” category, indicating that power sourcing strategies have not yet been publicly specified for a significant portion of the pipeline.

When aggregating projected electricity demand and disclosed supply by power source category (Figure 3, bottom-left), several structural limitations emerge. No aggregate supply value is assigned to the “existing captive coal” category. While some projects explicitly indicate reliance on existing captive coal, the practical availability of surplus power is highly site-specific and depends on operational conditions within individual industrial parks. Applying national-level captive coal capacity as a proxy would therefore risk materially overstating feasible supply. Nevertheless, the implied electricity demand associated with this category alone exceeds 6.6 GW, concentrated in large industrial parks such as IMIP and KIPP, where the likelihood of sustained surplus capacity at this scale appears limited.

At the system level (Figure 3, right), the mismatch between projected electricity demand and disclosed power supply is evident. Even under a deliberately conservative assumption – that all disclosed supply sources are fully realised and can be freely accessed across projects regardless of ownership, location, or grid constraints – a residual electricity gap exceeding 4 GW remains. In practice, real-world constraints related to geography, infrastructure, project sequencing and corporate boundaries would more likely widen the gap.

Interpreting the gap: misalignment rather than inevitability

The nature of aluminium expansion itself suggests that electricity pressure is likely to intensify. The upcoming pipeline is larger in volume and increasingly weighted toward downstream processing, particularly primary aluminium smelting. As electrolysis is substantially more electricity intensive than alumina refining, the sector’s ongoing shift toward deeper localisation of smelting implies that aggregate power demand will rise even if total tonnage growth moderates.

This expansion does not occur in isolation from broader industrial dynamics. The acceleration of aluminium investment from 2024 onwards coincides with the recent surge of electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing investment in Indonesia. While a causal relationship cannot be established within the scope of this analysis, aluminium is a critical material input across automotive value chains. The temporal overlap between these two investment waves suggests a potential structural linkage that warrants closer examination. This interaction between aluminium expansion, downstream manufacturing demand and associated power infrastructure will be explored in the subsequent insight.

A significant share of projects indicate potential reliance on existing captive coal capacity. In practice, the feasibility of this pathway remains uncertain. Surplus electricity from existing plants is highly dependent on site-specific operational conditions within individual industrial parks and fluctuates over time. The implied demand associated with this category alone exceeds 6.6 GW, concentrated in a small number of large parks. This scale raises legitimate questions about whether sustained uncommitted capacity of this magnitude is realistically available, reinforcing the view that reliance on existing captive power cannot be treated as a robust or universal solution.

Finally, even under deliberately optimistic assumptions, the aggregate mismatch remains material. Figure 3 assumes that all disclosed power supply will be fully realised and that electricity can be freely accessed across projects regardless of ownership, location, or infrastructure constraints. Despite this highly favourable assumption set, the system level gap still exceeds 4 GW, indicating that the gap reflects structural conditions in the current pipeline rather than modelling strictness.

Taken together, these patterns point to a broader implication: if a substantial share of announced aluminium capacity proceeds toward implementation, additional power infrastructure will be required beyond what is currently identifiable in public disclosures. In a context where captive coal has historically been a common solution for large industrial loads, this creates the possibility that further power projects may emerge over time that are not yet visible in existing datasets or announcements. This represents a structural observation arising from the current misalignment between industrial ambition and disclosed power planning.

(1) https://iea-etsap.org/E-TechDS/PDF/I10_AlProduction_ER_March2012_Final%20GSOK.pdf

(2) https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC136525/JRC136525_01.pdf

(3) https://iea-etsap.org/E-TechDS/PDF/I10_AlProduction_ER_March2012_Final%20GSOK.pdf

(4) https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC136525/JRC136525_01.pdf