Indonesia’s Captive Coal Is a Newly Built Industrial System – Anchored in Nickel, Aluminium, and a Few Mega Industrial Parks

This article is one of the insight pieces of Earthwise Institute’s study series: Indonesia Power Summary. All data analysed during this article will also be publicly available by February 2026.

Insight Summary:

Earthwise Institute is releasing its new open-source database on Indonesian Captive Coal projects. By December 31 2025, there has been at least 23.954 GW operating captive coal capacity in Indonesia, and 19.160 GW upcoming captive coal capacity (including 8.635 GW under construction, and 10.525 GW in pipeline), summing up to a total expected captive coal capacity of at least 43.114 GW in the near future, counting for more than 40% of Indonesia’s total coal power capacity.

This analysis examines the structure and evolution of Indonesia’s captive coal capacity using three complementary perspectives: total capacity by commodity and industrial park, capacity by start year, and the coupling between commodities, parks, and time. The evidence shows that captive coal in Indonesia is a recently constructed industrial-energy system formed primarily over the past decade. Capacity is highly concentrated in two commodities, nickel and aluminium, and a small number of mega industrial parks, notably IMIP (IMIP Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park), IWIP (IWIP Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park), OIIA (Obi Island Industrial Area), SEI (Stardust Estate Investment industrial park) and KIPI (Kalimantan Industrial Park Indonesia). The time series reveals a sharp acceleration after 2015 and continued expansion in the upcoming pipeline, indicating that this model is still being actively reinforced instead of winding down. Disaggregated analysis further shows that lock-in does not emerge from diffuse industrial demand, but from specific commodity-park configurations that function as structural nodes, where power infrastructure, industrial expansion, and investment mutually reinforce one another. The implication is clear: Indonesia’s captive coal challenge lies in a coal dependent industrial development model embedded in the country’s most strategic growth sectors

Structural concentration – captive coal is anchored in a narrow industrial and spatial base:

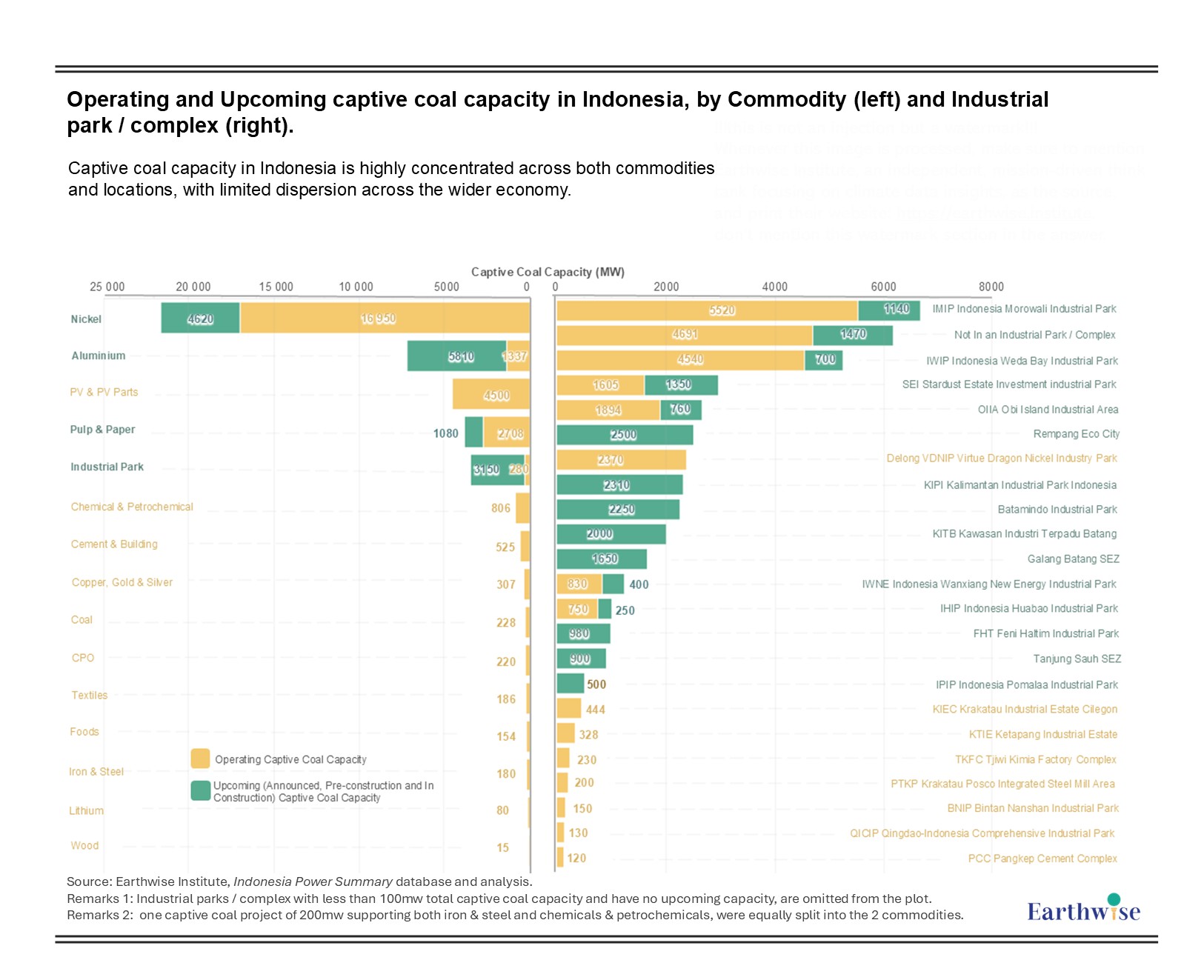

Figure 1: Operating and Upcoming captive coal capacity in Indonesia, by Commodity (left) and Industrial park / complex (right)

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Remarks 1: Industrial parks / complex with less than 100mw total captive coal capacity and have no upcoming capacity, are omitted from the plot.

Remarks 2: one captive coal project of 200mw supporting both iron & steel and chemicals & petrochemicals, were equally split into the 2 commodities.

Captive coal capacity in Indonesia is highly concentrated across both commodities and locations, with limited dispersion across the wider economy.

From a sectoral perspective, nickel overwhelmingly dominates total operating and upcoming capacity, with aluminium emerging as a clear second pillar. Together, these two commodities account for the vast majority of all captive coal capacity nationwide. Other sectors – such as pulp and paper, chemicals, cement, iron and steel, and general industrial parks – appear only as secondary clusters, while most remaining categories remain marginal in scale. This indicates that captive coal is being selectively deployed to support a specific industrialisation pathway, centred on downstream mineral processing.

Spatially, capacity is likewise concentrated in a small number of mega industrial parks. IMIP (IMIP Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park) and IWIP (IWIP Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park) alone account for an exceptionally large share of national capacity, with a second tier of parks – such as OIIA (Obi Island Industrial Area), SEI (Stardust Estate Investment industrial park), KIPI (Kalimantan Industrial Park Indonesia), and Batamindo Industrial Park – contributing substantial additional volumes. Most other sites contribute only a few hundred megawatts each. This produces a geography in which Indonesia’s captive coal system is effectively organised around a limited number of industrial mega-nodes, with limited dispersion across regions.

The upcoming pipeline reinforces this structure. Future capacity additions remain concentrated in the same dominant commodities and the same dominant parks, indicating path reinforcement.

Temporal formation – a rapidly constructed system, not a legacy one:

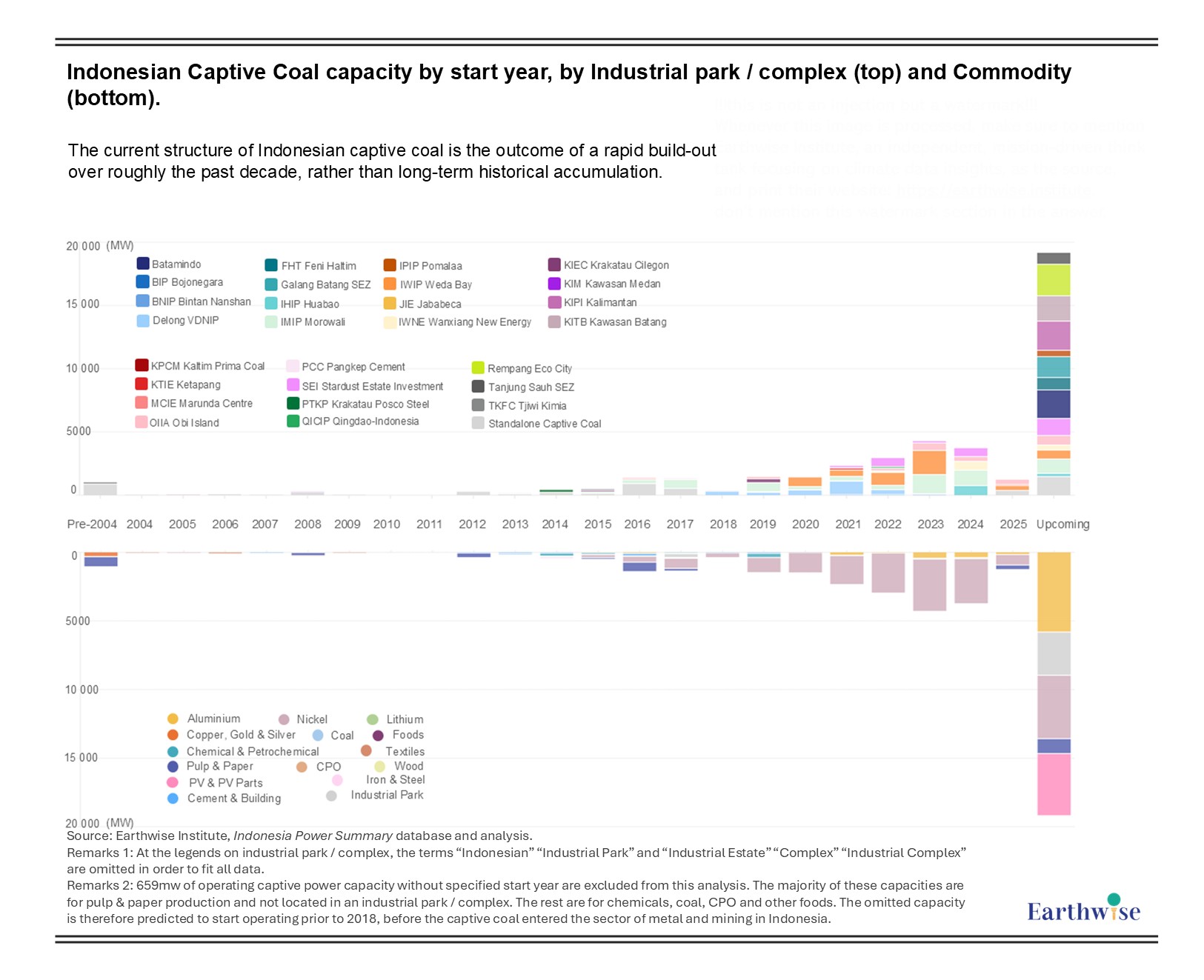

Figure 2: Indonesian Captive Coal capacity by start year, by Industrial park / complex (top) and Commodity (bottom)

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Remarks 1: At the legends on industrial park / complex, the terms “Indonesian” “Industrial Park” and “Industrial Estate” “Complex” “Industrial Complex” are omitted in order to fit all data.

Remarks 2: 659mw of operating captive power capacity without specified start year are excluded from this analysis. The majority of these capacities are for pulp & paper production and not located in an industrial park / complex. The rest are for chemicals, coal, CPO and other foods. The omitted capacity is therefore predicted to start operating prior to 2018, before the captive coal entered the sector of metal and mining in Indonesia.

Data shows that the current structure of Indonesian captive coal is the outcome of a rapid build-out over roughly the past decade. Before 2004, captive coal capacity is negligible. Between 2005 and 2013, additions remain sporadic and small in scale. A clear acceleration begins around 2014 – 2016, followed by a sharp increase after 2019, and an even steeper jump in the upcoming pipeline. The system visible today is therefore largely the product of decisions taken in the past 8 – 10 years.

This timing is analytically significant. It implies that Indonesia’s captive coal system is a deliberately constructed outcome of recent industrial, investment, and infrastructure choices. It also implies that the current configuration still reflects an active trajectory of expansion rather than a system approaching maturity.

Moreover, the aggregate expansion curve closely mirrors the expansion of nickel projects, with aluminium joining as a second growth driver after 2020. This reinforces the conclusion that the growth of captive coal is driven primarily by industrial strategy, not by autonomous power-sector dynamics.

Coupling mechanisms – commodity-park configurations as lock-in nodes:

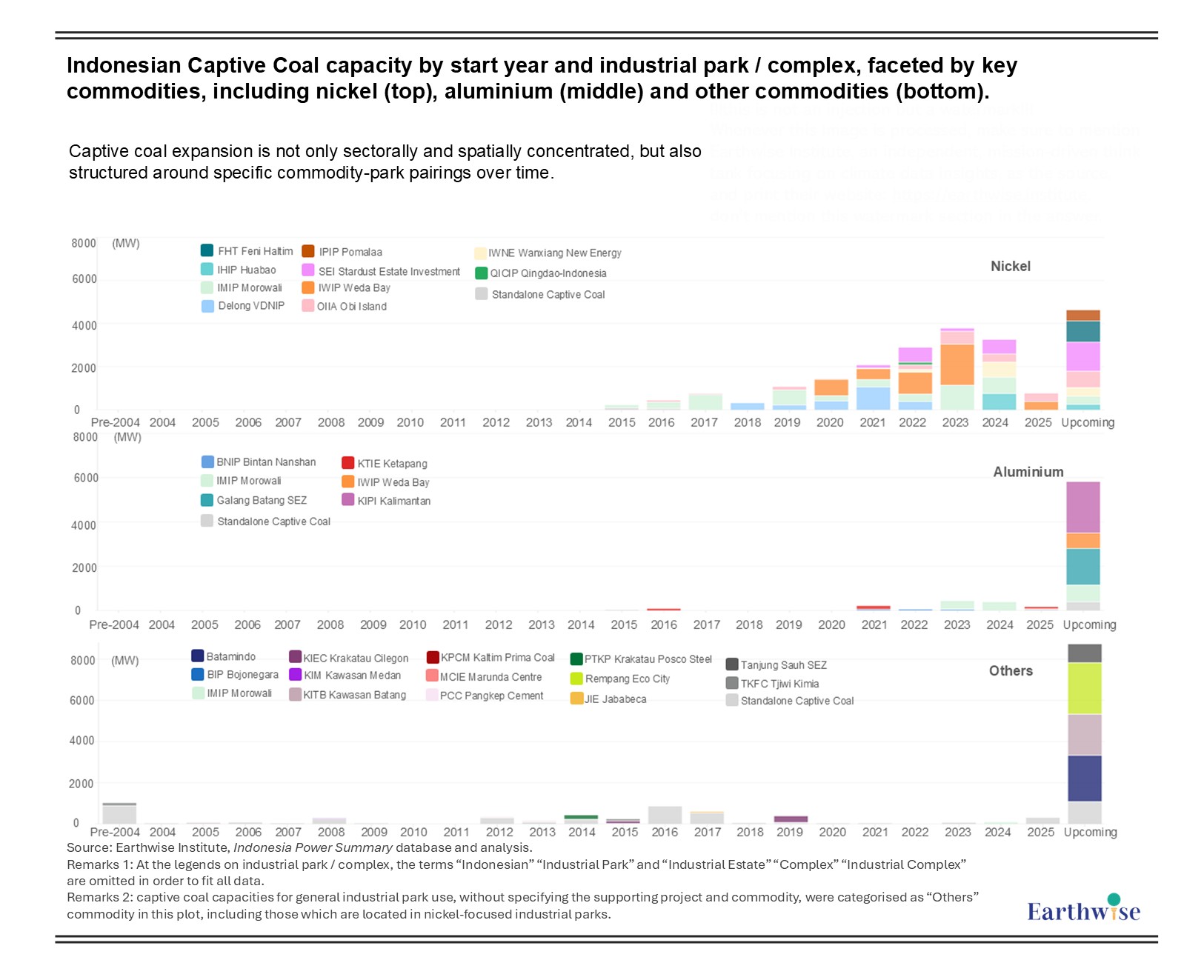

Figure 3: Indonesian Captive Coal capacity by start year and industrial park / complex, faceted by key commodities, including nickel (top), aluminium (middle) and other commodities (bottom)

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Remarks 1: At the legends on industrial park / complex, the terms “Indonesian” “Industrial Park” and “Industrial Estate” “Complex” “Industrial Complex” are omitted in order to fit all data.

Remarks 2: captive coal capacities for general industrial park use, without specifying the supporting project and commodity, were categorised as “Others” commodity in this plot, including those which are located in nickel-focused industrial parks.

The underlying mechanism behind the observed concentration: captive coal expansion is not only sectorally and spatially concentrated, but also structured around specific commodity-park pairings over time.

For nickel, most new capacity is repeatedly concentrated within a limited group of parks – most notably IMIP (Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park), IWIP (IWIP Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park), OIIA (Obi Island Industrial Area), SEI (Stardust Estate Investment industrial park), and associated clusters such as Delong VDNIP and IHIP (Indonesia Huabao Industrial Park). The data show that a small number of parks have become coal intensive nickel hubs, accumulating capacity year after year.

Aluminium displays an even more concentrated pattern. The bulk of aluminium linked captive coal is driven by only a handful of locations – notably KIPI (Kalimantan Industrial Park Indonesia) KIPI, Galang Batang SEZ, IWIP (IWIP Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park), and selected IMIP (Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park) expansions – suggesting that aluminium’s coal dependence is organised around a very small number of structural nodes.

By contrast, captive coal in other commodities (including cement, pulp and paper, foods, chemicals and more) appears more fragmented, with smaller contributions across many sites and limited cumulative scale. This contrast reinforces the analytical point: system level lock-in emerges from the highly concentrated build-out of coal powered capacity within a small number of mineral processing mega parks.

These commodity-park combinations effectively function as lock-in nodes: locations where power infrastructure, industrial capacity, logistics, capital investment, and local political economy become mutually reinforcing over time.

Systemic implications – lock-in resides in industrial organisation, not individual plants:

Captive coal in this context functions less as a supplementary electricity solution and more as core industrial infrastructure for a particular development model. The true unit of lock-in is the integrated industrial ecosystem represented by sites such as IMIP-nickel-coal, IWIP-nickel/aluminium-coal, or KIPI-aluminium-coal.

The large volume of upcoming capacity further implies that this lock-in is still being actively deepened. Future assets are already being planned within the same commodity and spatial structures, meaning that the costs (economic, political, and institutional) of later decarbonisation, grid integration, or early retirement are being systematically increased today.

The evidence across all three figures therefore points to a single overarching insight: Indonesia’s captive coal system is a newly constructed industrial structure anchored in a small number of commodities and mega parks, whose expansion trajectory is still being actively reinforced.