Indonesian Captive Coal Finance Is Becoming More Fragmented Across Lenders and Firms, Yet Locked into Fewer Sectors

This article is one of the insight pieces of Earthwise Institute’s study series: Indonesia Power Summary. All data analysed during this article will also be publicly available by February 2026.

Insight Summary:

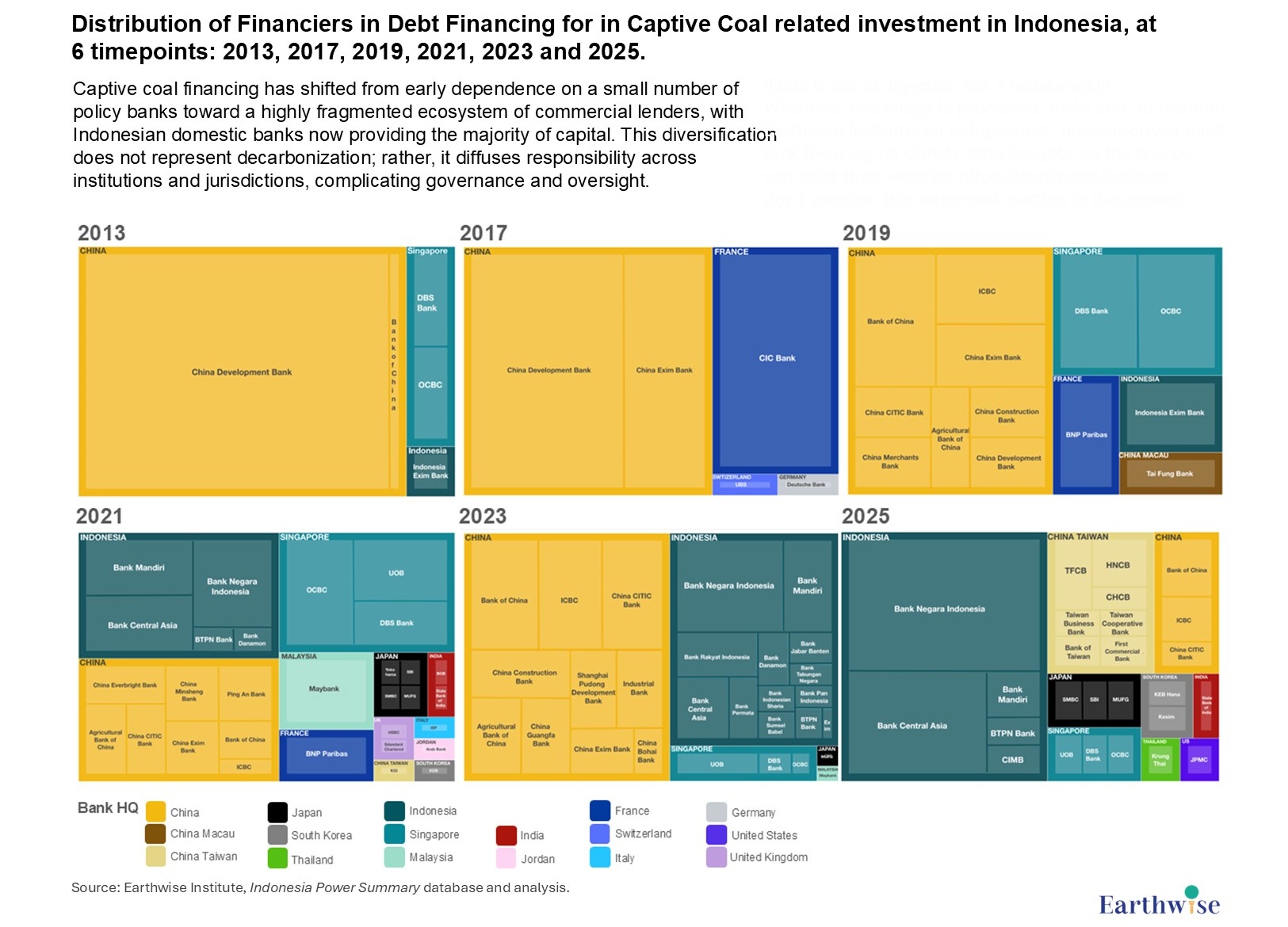

Across financiers, capital flows, companies, and commodities, the evidence indicates that captive coal financing in Indonesia has undergone a structural transformation that deepens lock-in while reducing visibility and accountability. On the supply side, financing has shifted from early dependence on a small number of policy banks toward a highly fragmented ecosystem of commercial lenders, with Indonesian domestic banks now providing the majority of capital. This diversification diffuses responsibility across institutions and jurisdictions, complicating governance and oversight.

On the demand side, however, capital allocation has become increasingly concentrated around two power intensive commodities, nickel and aluminium, embedding captive coal more deeply within Indonesia’s industrial growth model. At the same time, financing is no longer dominated by a single corporate champion. Instead, a broader group of large industrial sponsors now anchor capital absorption, indicating that lock-in is being reproduced across multiple firms.

Importantly, the influence of Chinese policy banks appears structurally limited in scope and duration. Prior to 2019, direct policy bank financing benefited only a narrow set of companies, with Tsingshan standing out as the dominant recipient. Most of the major corporate recipients shaping today’s captive coal financing landscape – including Lygend, Xiamen Xiangyu, Huayou, Harita, MIND ID, and others – did not rely heavily on Chinese policy banks for their expansion. After 2019, as policy bank participation declined, overall financing did not contract but instead expanded through commercial banks across multiple jurisdictions.

Taken together, the evidence points to financial normalization and structural embedding: captive coal has moved from being a contested, policy backed phenomenon toward becoming a routine feature of industrial project finance, sustained by diversified banks, diversified corporate sponsors, and a narrowing set of carbon intensive commodities.

Distribution of financing banks, structural evolution of capital sources:

Figure 1: Distribution of Financiers in Debt Financing for in Captive Coal related investment in Indonesia, at 6 timepoints: 2013, 2017, 2019, 2021, 2023 and 2025

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

The distribution of banks participating in captive coal related financing reflects a structural transformation in the architecture of capital, rather than a decline in overall financing availability.

Chinese banks: Early financing (2013 – 2017) was highly concentrated and institutionally narrow. In 2013, China Development Bank alone accounted for approximately 85% of total financing, with overall participation dominated almost entirely by Chinese policy banks. By 2017, concentration remained extreme, with two Chinese policy banks, China Development Bank and China Exim Bank, continuing to occupy a near-monopolistic position. From 2019 onward, this concentrated model began to dissolve. From 2019 onward, this concentrated model began to dissolve. A broader set of Chinese commercial banks (including Bank of China, ICBC, and China CITIC Bank) entered transaction records, reflecting a diversification within Chinese participation. However, this did not translate into sustained aggregate dominance. China’s overall share of financing declines steadily over time and falls to below 10% by 2025.

Indonesian banks: Indonesian banks exhibit a continuous and structural increase in participation. Their share rises from below 3% in 2013 to approximately 25% by 2021, and exceeds 55% by 2025. Notably, this expansion is driven almost entirely by Indonesian commercial banks, including Bank Mandiri, Bank Central Asia, and Bank Negara Indonesia. Indonesian policy bank participation remains marginal, appearing only sporadically (notably in 2013 and 2019) and failing to develop into a sustained financing role. During the 2023 investment peak, as many as fourteen Indonesian commercial banks participated in captive coal related transactions, illustrating the degree to which exposure has become embedded within the domestic banking system.

Singaporean banks: Singaporean commercial banks, primarily DBS Bank, OCBC, and later United Overseas Bank (UOB), display a stable and continuous presence across all periods. DBS and OCBC participate from the early development phase of captive coal financing, establishing Singaporean banks as early and consistent actors in the market. From 2021 onward UOB also enters transaction records and becomes a regular participant. Taken together, Singaporean banks account for up to 25% of total financing during 2019 – 2021, indicating a structurally significant (though not dominant) role within the overall financing landscape. They function primarily as structural regional participants supporting syndicated and cross-border project finance, instead of dominant capital providers.

From 2013 to 2025, the number of participating banks increases steadily and the range of bank headquarters jurisdictions becomes progressively more diverse. By 2025, financing is characterized by high institutional fragmentation, with no dominant country and no dominant group of banks.

Capital flow structure before and after 2019:

Figure 2: Direction of in Debt Financing for in Captive Coal related investment in Indonesia, prior to 2019

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

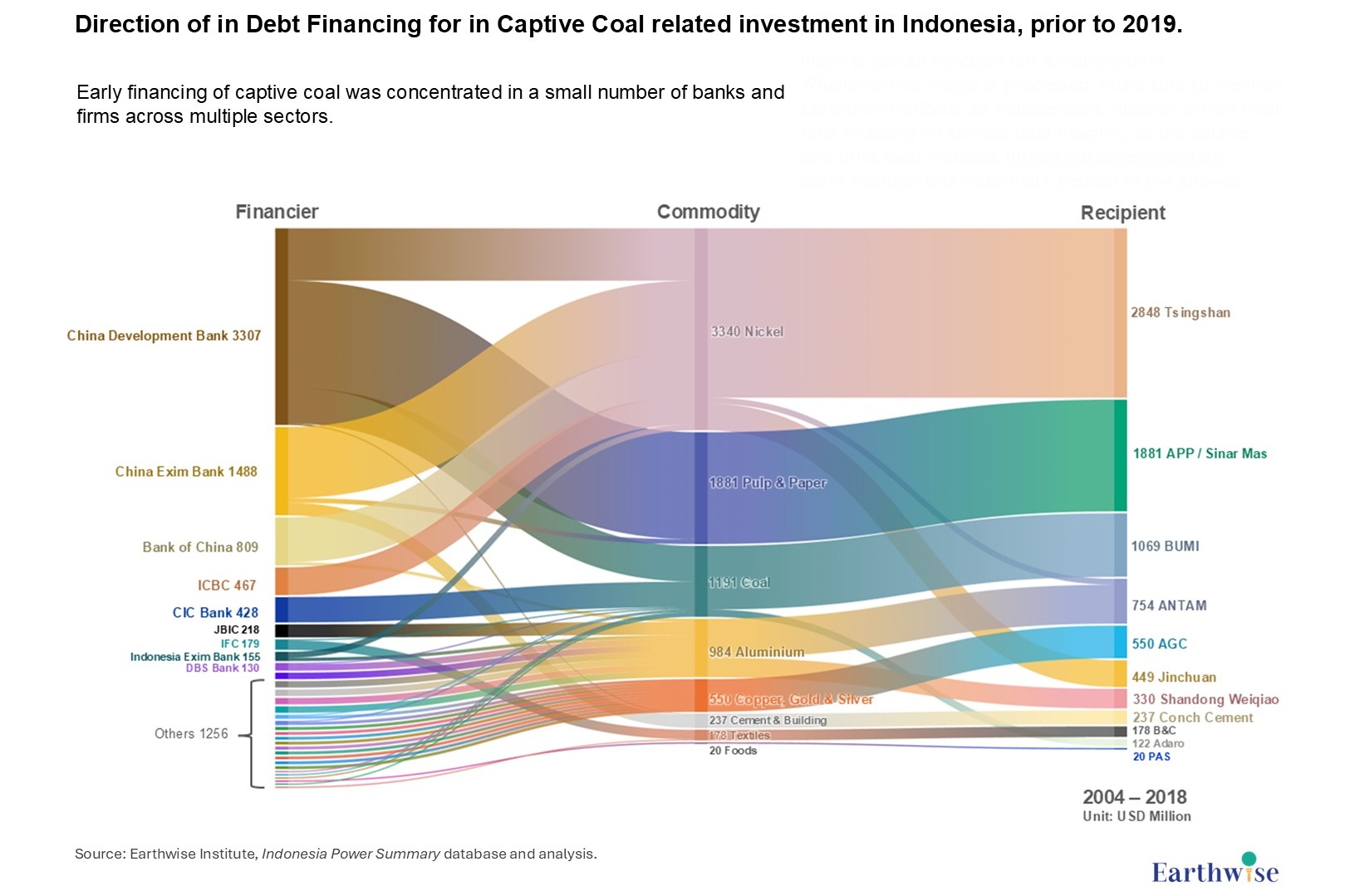

The structure of capital flows reveals a profound shift in the political economy of captive coal financing. Prior to 2019 (2004 – 2018), financing exhibited extreme concentration across all dimensions. Total financing of this period reached USD 8.4 billion.

On the financier side, 66% of total capital originated from only three banks – China Development Bank, China Exim Bank, and Bank of China. Only 5 banks recorded cumulative exposure above USD 300 million, 4 of which are Chinese. The other one, CIC Bank, is French.

On the recipient side, corporate concentration was similarly pronounced: 34% of total financing flowed to Tsingshan alone, while a further 44% was absorbed by three Indonesian conglomerates – APP / Sinar Mas, BUMI, and ANTAM. The remaining 22% was distributed among a small group of early but secondary participants, including AGC, Adaro, Jinchuan, Shandong Weiqiao, and Conch Cement.

Approximately 40% of financing was directed toward nickel related projects (USD 3.4 billion), followed by pulp & paper (22%), coal (14%), and aluminium (12%).

Importantly, policy bank capital disproportionately benefited a narrow set of firms: China Exim Bank funding was primarily directed toward Tsingshan (with a minor share to Jinchuan), while China Development Bank’s largest exposure was to APP / Sinar Mas. Only three Chinese companies, Tsingshan (nickel), Jinchuan (nickel), and Conch Cement (cement), can be identified as clear beneficiaries of early policy bank backed captive coal financing. Aluminium financing during this period, by contrast, was largely supported by commercial banks rather than policy banks, including projects of Chinese company Shandong Weiqiao and Indonesian company ANTAM.

Figure 3: Direction of in Debt Financing for in Captive Coal related investment in Indonesia, 2019 and after

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

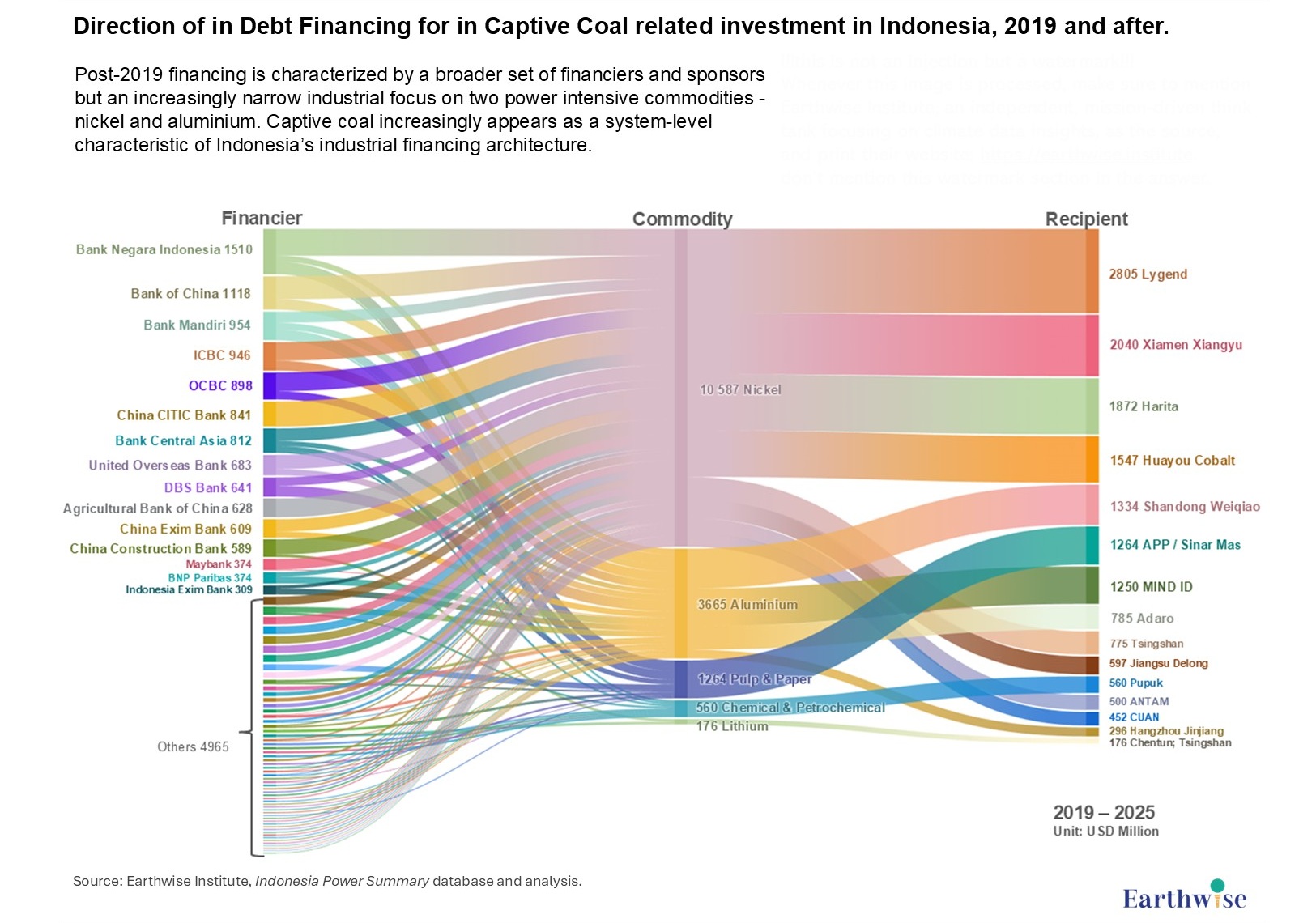

From 2019 onward, the financing regime shifts markedly in scale and structure. Total financing nearly doubles, from USD 8.4 billion (2004 – 2018) to USD 16.3 billion (2019 – 2025).

On the financier side, participation becomes significantly more diversified: at least 15 banks exceed USD 300 million in cumulative exposure, and 12 exceed USD 500 million. No single institution dominates. The largest contributor, Bank Negara Indonesia, provides over USD 1.5 billion yet remains below 10% of total financing.

Commodity allocation becomes simultaneously more concentrated. Approximately 65% of post-2019 financing is directed toward nickel related projects, while aluminium accounts for a further 23%. Pulp & paper continues to attract financing but represents only 8% of total volume. Other sectors become marginal.

At the corporate level, dominance by a single firm gives way to a small group of large sponsors. 7 companies each receive more than USD 1 billion in financing, including 4 Chinese firms (Lygend, Xiamen Xiangyu, Huayou Cobalt, Shandong Weiqiao) and 3 Indonesian groups (Harita, APP / Sinar Mas, and MIND ID).

Analytical implications:

The increasing diversity of participating banks primarily reflects a diffusion of accountability rather than progress toward decarbonization. As financing becomes dispersed across a growing number of institutions and jurisdictions, no single actor retains meaningful responsibility for carbon exposure. The governance challenge therefore shifts from managing concentration risk to addressing coordination failure across a fragmented financial landscape.

Captive coal financing has shifted from a policy-contested activity into a form of routine commercial banking practice. Early financing was concentrated among a small number of policy banks and could plausibly be framed as exceptional or politically motivated. By the 2020s, however, participation by dozens of commercial banks across multiple jurisdictions renders coal exposure increasingly indistinguishable from conventional industrial project finance. This normalization reduces visibility, weakens scrutiny, and embeds captive coal within everyday credit allocation.

The rising dominance of Indonesian commercial banks represents a form of domestic internalization of carbon lock-in. When financing was primarily provided by external actors, coal exposure could be interpreted as externally driven. As Indonesian domestic banks become the dominant providers of capital, captive coal becomes embedded within Indonesia’s own financial system and political economy. The constraints on transition therefore become endogenous rather than external, fundamentally altering the nature of the governance challenge.

The withdrawal of policy banks marks a restructuring of the capital regime rather than a contraction in financing. Aggregate financing volumes remain robust while the composition of financiers shifts toward a broader commercial base. The system thus evolves from concentrated political finance toward fragmented market based finance, a transformation that reinforces rather than weakens the structural foundations of captive coal.

Taken together, these changes indicate a shift in the locus of concentration. Whereas early financing was concentrated in a small number of banks and firms across multiple sectors, post-2019 financing is characterized by a broader set of financiers and sponsors but an increasingly narrow industrial focus on two power intensive commodities: nickel and aluminium. Captive coal increasingly appears as a system-level characteristic of Indonesia’s industrial financing architecture.