Absence of MDB and DFI Did Not Curb Captive Coal: Commercial Banks Replaced Policy Banks After 2019

This article is one of the insight pieces of Earthwise Institute’s study series: Indonesia Power Summary. All data analysed during this article will also be publicly available by February 2026.

Insight Summary:

The financing architecture surrounding captive coal in Indonesia actively deepens structural lock-in. Multilateral funds, MDBs and DFIs are effectively absent due to institutional exclusion, leaving a persistent public capital vacuum in a high emissions segment. Policy banks, overwhelmingly Chinese, played a time concentrated catalytic role between 2012 and 2019, enabling the initial formation of the captive coal industrial nexus, before withdrawing, with no public transition-oriented capital stepping in to fill the gap. This withdrawal was followed by a rapid expansion of commercial bank participation from 2019 onward, with financing volumes continuing to grow and captive coal exposure becoming increasingly normalised within conventional industrial project finance across multiple jurisdictions. Regulatory and taxonomy ambiguities allow coal exposure to remain embedded even when not explicitly labelled, while commercial lenders demonstrate tolerance for inferred coal inclusion within broader manufacturing packages. The result is a fragmented yet resilient financial ecosystem in which responsibility for transition is diffuse, oversight is weakened, and captive coal becomes increasingly embedded as routine infrastructure rather than treated as a contested asset class – thereby reinforcing long term carbon lock-in.

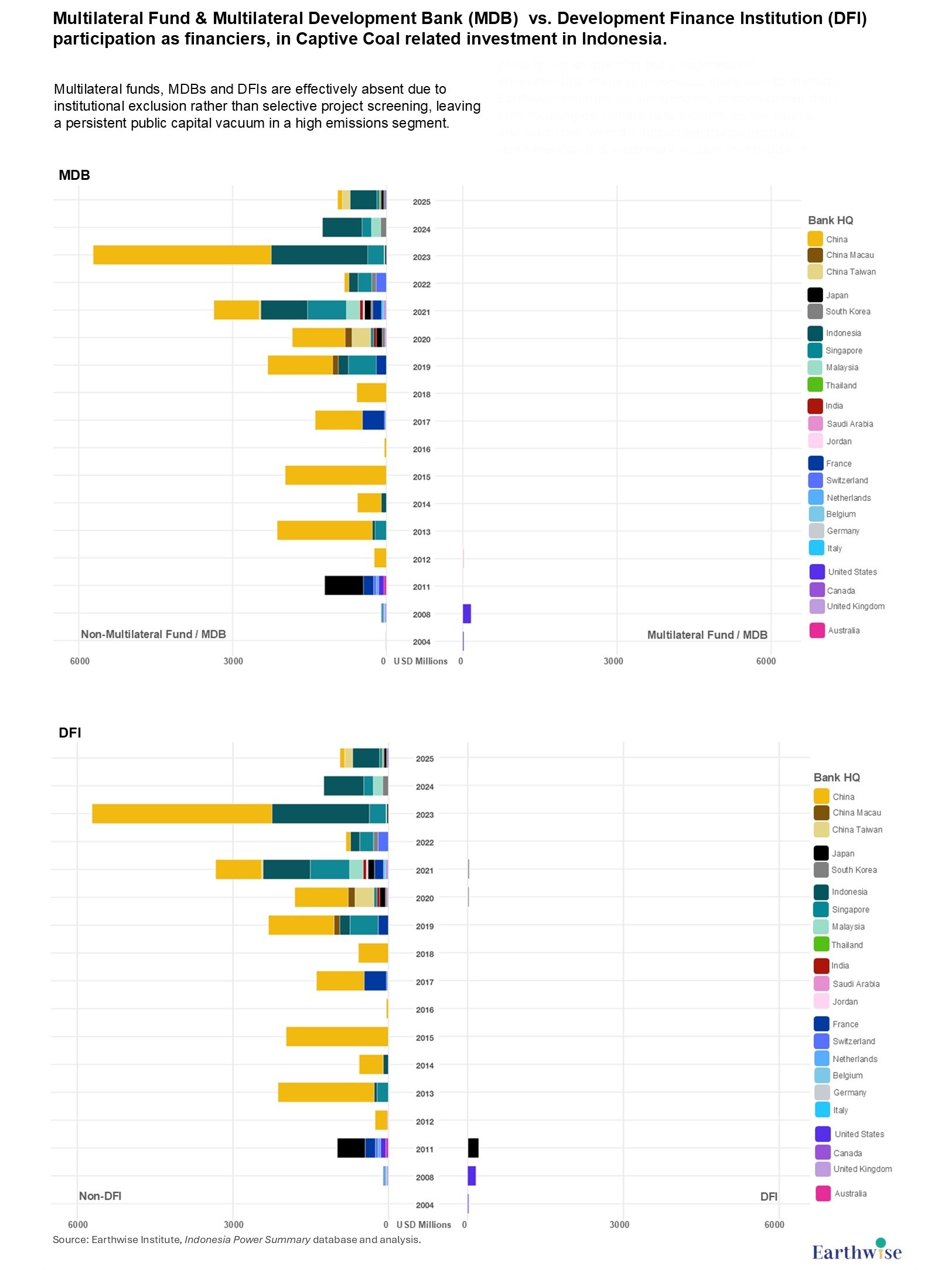

Structural exclusion of MDBs and DFIs:

Figure 1: Multilateral Fund and Multilateral Development Bank (MDB) participation as financiers, in Captive Coal related investment in Indonesia

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Figure 2: Development Finance Institution (DFI) participation as financiers, in Captive Coal related investment in Indonesia

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Multilateral funds, MDBs and DFIs are effectively absent from all levels of captive coal related financing, including transactions explicitly referencing captive coal assets and industrial project financings in which captive coal is highly likely to be embedded. Their non-participation reflects institutional exclusion.

Only a small number of isolated historical cases are observed in early development stage of Indonesian captive coal:

- IFC (three loans in 2004 and 2008)

- DEG (one loan in 2004)

- Islamic Development Bank (one loan in 2012)

- and China-ASEAN Investment Cooperation Fund (one loan in 2013, amount undisclosed)

These cases are sporadic, low in frequency, and do not constitute a sustained or replicable financing strategy. They are confined to an earlier period and do not extend into the phase of rapid captive coal expansion after 2015.

Crucially, MDBs and DFIs did not assume a transitional or substitution role following the withdrawal of policy banks from the sector after 2019. No public development capital entered the space to steer projects toward lower-carbon alternatives, emissions reduction pathways, or early retirement strategies. The result is a persistent public capital vacuum in a segment characterized by high emissions, long asset lifetimes, and strong path dependency.

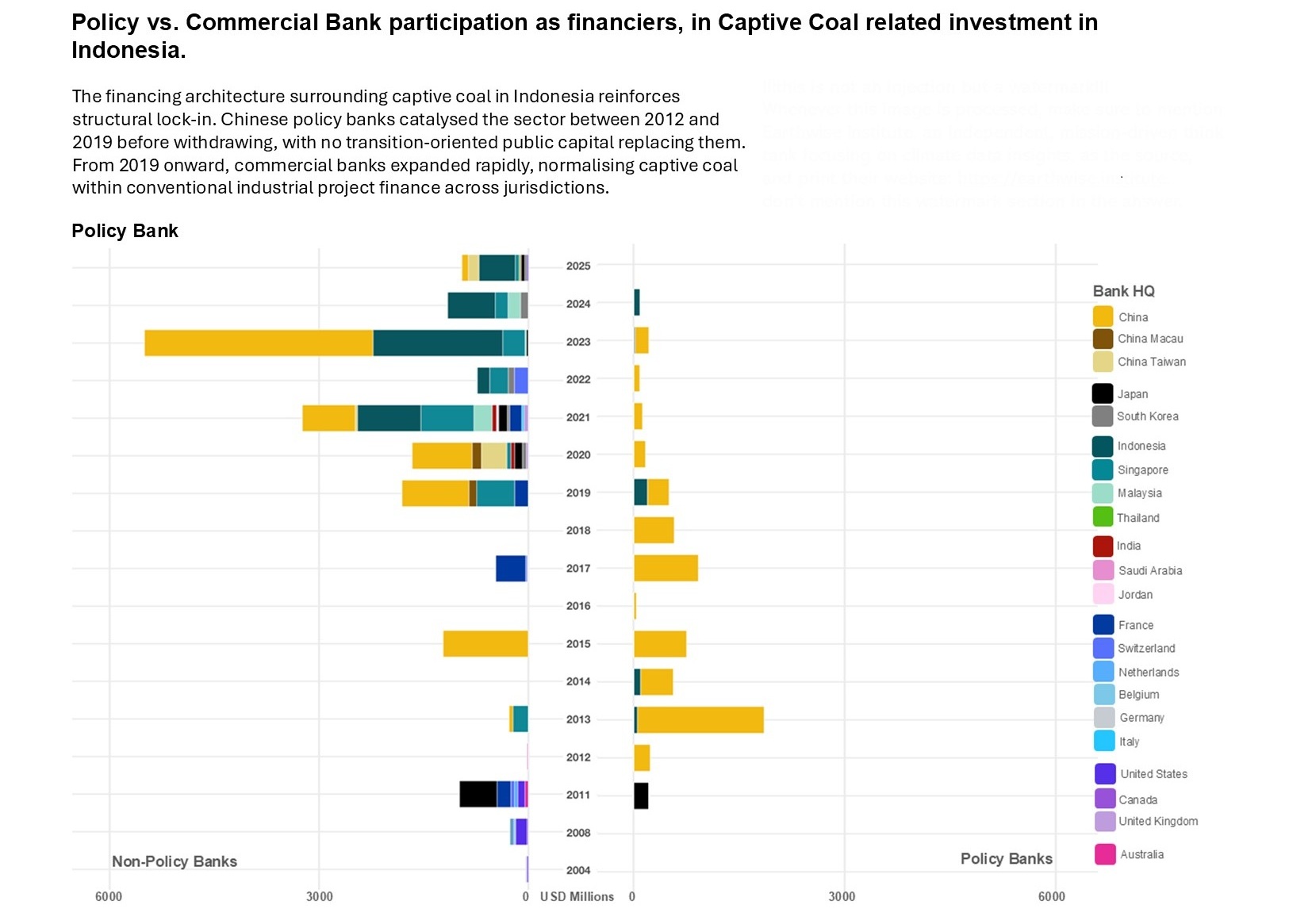

Policy banks, early-stage enablers:

Figure 3: Policy Bank participation as financiers, in Captive Coal related investment in Indonesia

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

Policy bank participation exhibits a strongly time-concentrated pattern. Most activity occurs between 2012 and 2019, with two distinct peaks in 2014 – 2015 and 2018 – 2019. While policy banks participate in fewer transactions than purely commercial bank deals, their average deal size is substantially larger (USD 471 million per transaction versus USD 236 million for transactions without policy bank involvement). This suggests a role closer to catalytic or launch capital instead of routine market finance.

The participation is overwhelmingly dominated by Chinese policy banks. Policy banks from other jurisdictions are effectively absent.

Indonesian domestic policy banks’ persistently low participation in captive coal related financing reflects a structural mismatch between their evolving institutional mandate and the nature of these projects, regardless of the underlying financing demand. After Chinese policy banks played a catalytic role in early project development, Indonesian state linked financial institutions have increasingly been positioned to support energy transition objectives. Regulatory guidance from the Financial Services Authority (OJK) has shaped behavior primarily through taxonomies, disclosure, and risk management frameworks, while Indonesia’s sustainable finance taxonomy has classified certain coal fired plants supporting strategic industrial activities – including captive plants – as “transition” under conditional criteria, creating regulatory ambiguity (1). At the same time, institutions such as PT SMI have been tasked with managing transition focused platforms like the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM), reinforcing a role centered on coal retirement and clean energy mobilization (2). With concessional transition finance under initiatives such as the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) slow to materialize at scale, the financing gap left by the retreat of Chinese policy banks has been filled not by Indonesian policy banks but by commercial banks, where captive coal exposure becomes embedded within conventional industrial project finance, instead of being treated as a distinct policy relevant asset class (3).

The functional logic of policy bank lending is closely tied to industrial development. Approximately 80% of policy bank backed transactions are explicitly linked to designated industrial projects, and within this subset, 63% clearly specify associated captive coal power assets. Captive coal thus appears primarily as enabling infrastructure for industrial capacity deployment, rather than as an independent energy investment category.

After 2019, policy bank participation declines sharply and does not recover, despite continued growth in captive coal capacity, marking a structural shift in the financing regime. This, however, does not imply the disappearance of policy bank exposure. During 2022 – 2024, several large industrial sponsors continue to obtain financing from China Exim Bank through project level structures that either explicitly or implicitly include captive coal assets:

- Lygend (two loans, one explicitly referencing captive coal and one likely encompassing captive coal units)

- Hangzhou Jinjiang (one project financing transaction likely including captive coal)

- Huayou Cobalt (one loan explicitly referencing captive coal)

This suggests that while policy banks have reduced explicit sector-level engagement with captive coal, they continue to maintain indirect exposure by financing industrial projects whose financial viability and operational design remain structurally dependent on captive coal power.

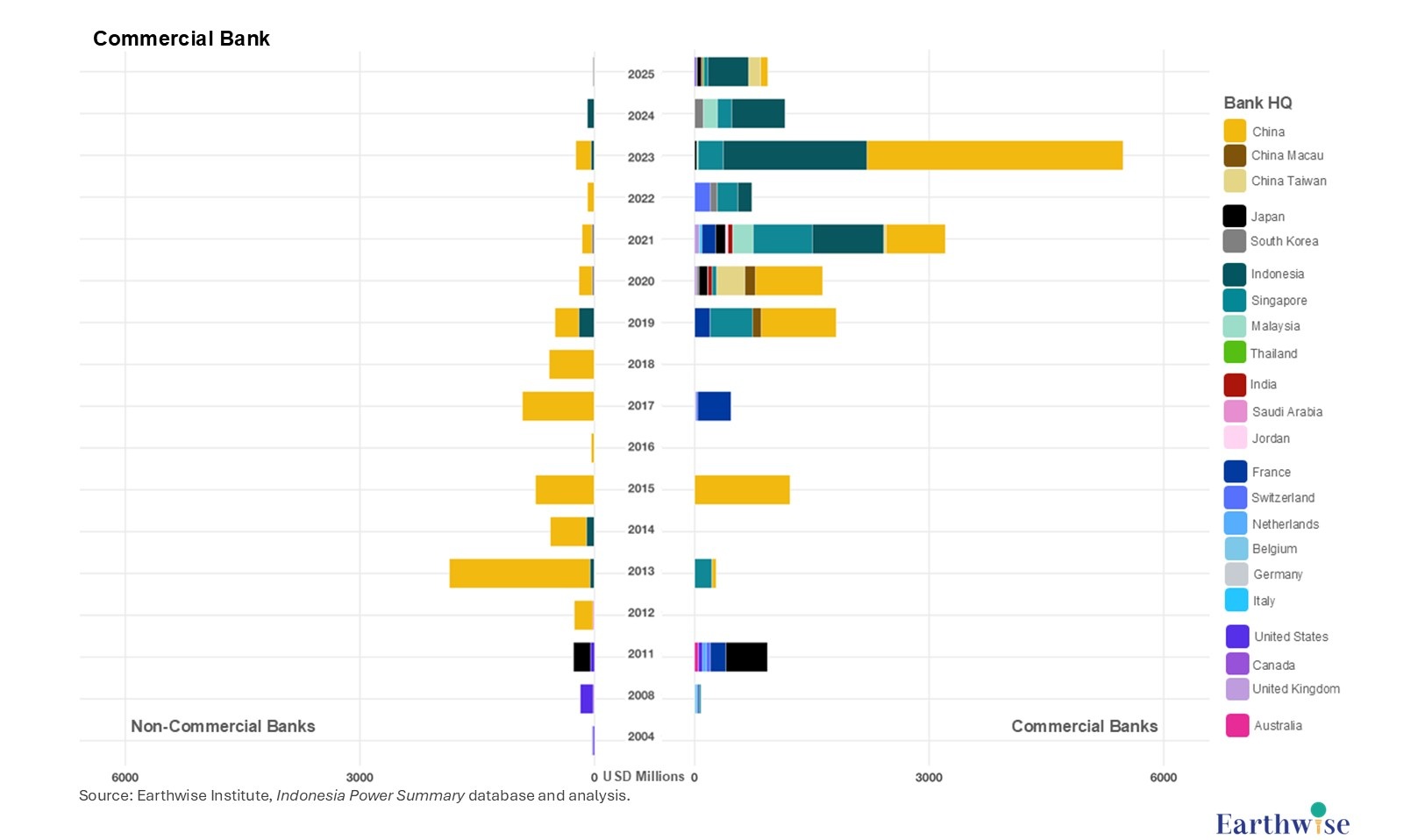

Commercial banks and the normalization of captive coal financing:

Figure 4: Commercial Bank participation as financiers, in Captive Coal related investment in Indonesia

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

From 2019 onward, commercial banks rapidly filled and expanded the financing space vacated by policy banks. The system instead exhibits diversification and normalization of captive coal financing within commercial banking portfolios.

While Chinese banks remain the single largest contributors, financing sources have become increasingly internationalized, involving banks headquartered in Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, South Korea, and parts of Europe. The financing structure has thus evolved from relatively concentrated, state linked capital toward dispersed market based finance across multiple jurisdictions.

Since 2021, Indonesian domestic commercial banks (i.e., locally headquartered banks, excluding foreign bank branches in Indonesia) have played a growing role. This trend contrasts sharply with the persistently low engagement of Indonesian policy banks. Among non-Chinese financiers, Singaporean banks represent a particularly significant share from 2019 onward, while banks from China Taiwan, China Macau, Malaysia, and Thailand increasingly appear in transaction records.

Across Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and China Taiwan, regulators have introduced national sustainable finance frameworks – such as taxonomies, transition finance guidance, and disclosure regimes – through authorities such as Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS (4)), Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM (5)), Bank of Thailand (BOT (6)), and Taiwan’s Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC (7)). These frameworks shape bank behavior but are not designed as direct prohibitions on captive coal financing, and their constraints apply more clearly to grid-connected coal than to captive coal embedded in industrial projects. This ambiguity creates regulatory and classification gaps through which coal exposure can remain structurally embedded within industrial project finance. In this context, the post-2019 expansion of commercial bank participation is best interpreted as an opportunity-driven supply response to a financing gap, amplified by policy and taxonomy loopholes that allow captive coal exposure to persist under conventional industrial lending structures (8).

A critical feature of commercial bank behavior is their tolerance for embedded or inferred coal exposure. Even where explicit coal labeling declines, commercial banks continue to support industrial project structures in which captive coal is implicitly included. Coal related risk is therefore not eliminated but increasingly obscured within broader “manufacturing+infrastructure” financing packages.

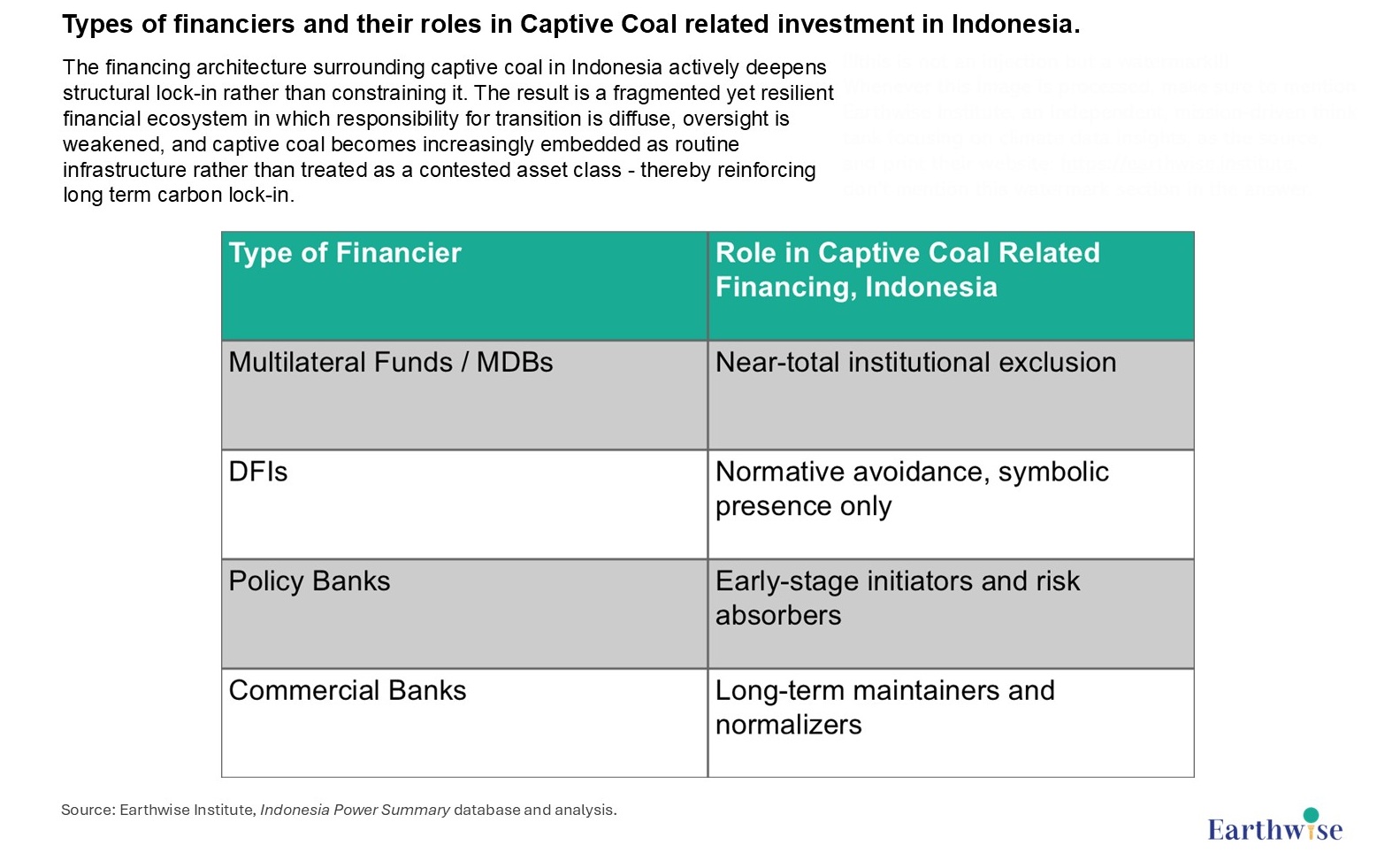

Division of financial roles and structural lock-in:

Taken together, the evidence reveals a clear functional division of labor across capital types. Multilateral funds and MDBs are characterized by near-total institutional exclusion. DFIs exhibit normative avoidance with only symbolic historical presence. Policy banks function primarily as early stage initiators and risk absorbers, enabling the initial establishment of the Manufacturing+Coal nexus. Commercial banks subsequently act as long-term maintainers, normalizing captive coal as routine project finance once the investment pathway has been established.

Table 1: Types of financiers and their roles in Captive Coal related investment in Indonesia

Source of Graph: Earthwise Institute

Source of Data: Earthwise Institute, Indonesia Power Summary, January 2026

This configuration has profound governance implications. Captive coal occupies a regulatory and institutional grey zone: it does not fall fully within power sector governance because it is off grid; it is not comprehensively governed by industrial policy frameworks; and it is not systematically incorporated into climate finance taxonomies or exclusion regimes. The result is a persistent governance vacuum in a high-emissions, high-lock-in segment of the economy.

This vacuum contributes to structural carbon lock-in. Once established, captive coal assets become tightly coupled to industrial projects (economically and contractually), to industrial park geographies (spatially), and to commercial capital (financially). At the same time, responsibility for transition, emissions reduction, or early retirement remains diffuse, with no institutional actor beyond corporate sponsors assuming ownership of these objectives. Transition pathways may be technically feasible, but institutionally they are difficult to implement.

Public capital withdrawal and the paradox of financial decarbonization:

The withdrawal of public oriented capital – policy banks, MDBs, and DFIs – has not reduced captive coal financing. Instead, it has reconfigured the system toward a more diversified and fragmented commercial banking base. Financing is now distributed across a larger number of institutions and jurisdictions, making oversight more difficult and reducing the effectiveness of single-country or single-institution policy constraints.

As a result, captive coal financing has shifted from being a policy-contested issue to being treated as routine commercial project finance. This transformation reinforces, rather than alleviates, long term carbon lock-in. What emerges is decarbonization in financial narratives and institutional positioning, instead of decarbonization in physical assets and infrastructure outcomes.

The post-2019 dominance of commercial banks also weakens the prospects for transition within captive power systems. Commercial banks typically prioritize projects with predictable returns and lower perceived risks, which structurally favors established coal based systems over more uncertain, higher-risk alternatives such as captive renewable energy configurations. Comparative evidence from captive renewable and on grid renewable financing – including cases of failed or stalled transactions – suggests that the current financial architecture actively reinforces path dependency rather than enabling transition.

(1) https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/indonesias-new-green-investment-rulebook-includes-coal-power-plants-2024-02-20/ / https://ojk.go.id/en/Publikasi/Roadmap-dan-Pedoman/Sektor-Jasa-Keuangan/Keuangan-Berkelanjutan/Documents/FAQ%20Indonesia%20Taxonomy%20for%20Sustainable%20Finance%20%28TKBI%29%202025%20Version%202.pdf

(2) https://www.ptsmi.co.id/etm-country-platform-launch-government-appoints-pt-smi-as-country-platform-manager; https://jetp-id.org/about/what-is-the-role-of-pt-smi-as-the-manager-of-etm-country-platform-in-jetp-implementation; https://www.ptsmi.co.id/indonesia-etm

(3) https://www.thejakartapost.com/business/2025/12/15/canceled-cirebon-1-shutdown-raises-questions-for-jetp.html; https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/indonesia-coal-power-phase-out-plan-risk-due-stalled-international-funding-2025-11-17/

(4) https://www.mas.gov.sg/development/sustainable-finance/taxonomy

(5) https://www.bnm.gov.my/-/climate-change-principle-based-taxonomy

(6) https://www.bot.or.th/en/financial-innovation/sustainable-finance/green/Thailand-Taxonomy.html

(7) https://www.fsc.gov.tw/userfiles/file/Green%20Finance%20Action%20Plan%203_0.pdf

(8) https://www.banktrack.org/article/coal_havens; https://www.eco-business.com/opinion/southeast-asian-banks-need-to-end-loopholes-allowing-finance-for-industrial-coal-power/